First things first: It is pronounced “Ain’t” Mae.

Writing about family is hard for me. Things seen through the eyes of a small boy are clouded by the years and the experiences that come later in life; when we were little we all looked for the best in people, the goodness we hoped for in the people that meant the most to us. My memories of Aunt Mae revolve around her farm and my days there; the ensuing years have only strengthened my love and admiration for her and that place, and that moment in time.

Probably the greatest gift my parents gave me when I was growing up was to expose me to their families. This was a history lesson in the truest sense of the word, a hands-on experience that today I value as much as any later education I received. To honestly assess one’s family is to take a hard look at yourself; sometimes this is a tough pill to swallow but the truth is always better than fiction, in writing and in life. My bunch would make one hell of a book.

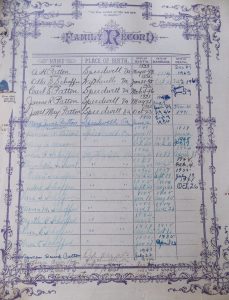

My grandmother’s sister, my great aunt, Mae Schaffer was born on January 19, 1888 and married Tom Pearman on August 13, 1908. She and Tom had 40 years together before he died. My first memory of her, in the summer of 1964, was delicious terror; as I came through the gate into the farmyard she greeted me, short and gray, with a flopping headless chicken in one fist and a hatchet in the other, with an apron blotched with blood, and a black eyepatch where her left eye should have been. The eye was lost, I found out later, when she was a teenager, racing horses one dark night with the man she would eventually marry, when a red cedar limb caught her unaware. My impression of her at the time was that she was as tough as a pine knot and that her piercing gaze missed nothing. She knew we were coming to visit and that morning was killing some chickens for my dinner; for the first time in my short life (I was 10 years old) I was truly impressed–and fried chicken took on a whole new meaning.

My grandmother’s sister, my great aunt, Mae Schaffer was born on January 19, 1888 and married Tom Pearman on August 13, 1908. She and Tom had 40 years together before he died. My first memory of her, in the summer of 1964, was delicious terror; as I came through the gate into the farmyard she greeted me, short and gray, with a flopping headless chicken in one fist and a hatchet in the other, with an apron blotched with blood, and a black eyepatch where her left eye should have been. The eye was lost, I found out later, when she was a teenager, racing horses one dark night with the man she would eventually marry, when a red cedar limb caught her unaware. My impression of her at the time was that she was as tough as a pine knot and that her piercing gaze missed nothing. She knew we were coming to visit and that morning was killing some chickens for my dinner; for the first time in my short life (I was 10 years old) I was truly impressed–and fried chicken took on a whole new meaning.

I have written before about Aunt Mae’s Four Winds Farm, the 798 acres in Wythe County, Virginia, near Porter’s Crossroads. Two of those stories appeared in Sporting Classics Magazine a few years ago, and if you have interest let Kelley St Germain know and perhaps I can post reprints of them here. What I found on that piece of ground all those years ago was a glimpse of Appalachian life that we will never see again.

I could try to make it romantic and wistful but that would only cheapen the memory; what I was being taught, without me knowing that I was learning anything, was subsistence farming in the truest sense. What went on at that farm at that time was life, being lived as it had to be lived, with the deep true lessons of human faith and commitment to family. For me it was as if the rest of the world did not exist once I walked through the whitewashed gate into that farmyard; and I can remember every detail of it as if it were yesterday. Over the years Aunt Mae taught me how to butcher hogs and how to turn them into smoked hams and bacon and sausage, how good cold buttermilk can be on a hot summer day, why the cow had to be milked and the eggs collected. She could shoe a horse, make apple butter in big copper kettles, play the fiddle and sing like an angel. She spoiled De-Con (her big orange tom cat) and little boys that hung around her kitchen to watch her biscuits brown in the wood cook stove. She kept the Schaffer family Bible, and she left that Bible to me when she crossed the river; when she died it was her only possession in this world.

My admonition to most people I meet is always the same; write down your memories of your life. I would give anything I have to be able to go back and ask Aunt Mae about her childhood, to one more time hear her cuss the hawk that killed her turkeys (and that she shot stone dead with the old Fox shotgun), and to see her, one more time, standing fists on hips in the door of that smokehouse, smiling at me as I carried those fresh hams up to her.

The best way I know to honor her is to pass her on to you.