As the story goes, the subject of today’s podcast was 35 years old before he ever used a camera. He left his Appalachian home during the Depression for the promise of a steady paycheck and landed in Detroit, Michigan, where, as he liked to say, “Henry Ford was paying us hillbillies five bucks a day to build that town.”

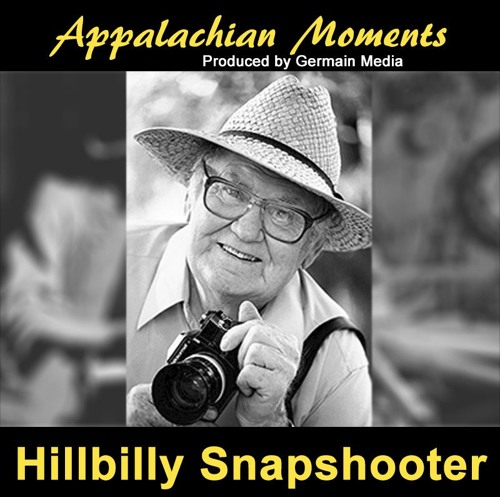

Rather than labor in a factory, he settled in as a night watchman at a department store. He befriended the advertising photographers who worked late at night, regaling them with tales from his home in Cumberland Gap, Tennessee. “Hillbilly,” as the photographers nicknamed him, loved to sit and watch them shoot.

The first time Hillbilly Snap Shooter Joe Clark ever touched a camera, he was leaving Detroit to head home for a family funeral. One of the store’s photographers handed him a $12 folding Kodak and three rolls of film, and said, “Hillbilly, since you’re always telling such big tales about your kinfolk, let’s see you prove it.”

Joe had the last and enduring laugh because ultimately Life magazine was so impressed with his pictures of the mournful mountain funeral in the rain, that it published a 14-picture spread in 1940.

Folks in Tennessee say Clark’s loyalty to his home earned him passage into the private lives and traditions of a proud people who had grown wary of outsiders. His snapshots – Joe scoffed at the word photos – evoked the dignity of the mountain dwellers of Appalachia, and for that, Clark became a kind of folk hero throughout the hills and hollers.

He didn’t like the depictions of grief and suffering that photographers of the day often recorded in and around his ancestral home. Clark sought only to show the dignity of country folk living off the land, caring for their own, and celebrating life’s passage. What pleased Clark more than anything was if the person in his snapshot liked it.

Despite the fact that National Geographic, Look, Newsweek. Esquire, and the Saturday Evening Post ran his photos, Clark never acted like a big-time photographer, um, snapshooter. He was always just Joe.

Beginning in 1956, Clark’s black and white images chronicled life in Lynchburg, Tenn., and for decades his work was featured in Jack Daniels advertising worldwide.

Around Lynchburg, in the barns, by the still house, and beside the barrel trucks, Joe greeted folks by name. He shared laughs and stories. Everyone soon forgot about the camera and the master in their midst

Today, his collection of iconic photos is worth an estimated $1.6 million.

For all his fame, however, Joe never let go of the mountains, and he lamented the disappearing culture he witnessed whenever he returned to east Tennessee. He said, “Those old days had their drawbacks but for those of us who lived them, they also have a host of fine memories. As long as a body had an axe, there was no need to worry about fuel or energy shortages. You just chopped yourself a big pile of wood and dared winter to do its worst.” Amen to that Joe Clark!

If you’d like to hear the audio version of this blog post, please click the link below and as always, thank you for liking, commenting and sharing this post with your friends!