Pigs have personalities and a broad range of emotions. They can be playful, spiteful, grouchy, vengeful, frisky, loving, and hateful. I know because I have grown to appreciate many pigs personally and I can still recall several of my best pig friends.

There are many different pig breeds: Yorkshires, Hampshires, Durocs, Old Spots, Landraces, and several flop-eared Chinese varieties. We limited our herd almost exclusively to the first three varieties, Yorkshires, Hampshires, and Durocs. The first two, and the ones we favored most, are descended from England, while the Durocs likely originated in Africa and were refined in the United States. Yorkshires are long, white hogs with perky ears. Hampshires are almost always black with white shoulders and ears that stand up. Their disposition is usually more ill-mannered, and they are quick to anger. Durocs are short red animals with ears that are prone to droop. Many of the other droopy-eared varieties, of which we had none, are of Chinese descent. Almost all the big, white hog breeds are mixed with Landrace. Another less common breed, the (Gloucestershire) Old Spots, were older and sometimes mistaken for Hampshires primarily because of their black and white markings, despite their distinctive mottled black spots.

Humans have long appreciated the companionship and taste of pigs and they were likely domesticated long before cats or dogs. Pigs are self-aware and can defend for themselves quite well. A cornered hog will charge, and their powerful jaws can snap a man’s long bones with ease. It is not commonly known that pigs cannot make vertical bites; they must turn their heads to the side in order to bite for effect. Remember that useful tip should you ever find yourself in a hog fight. Domesticated pigs have large lower canine tusks, along with 42 other teeth and, just like their feral cousins, they are proficient at inflicting nasty wounds.

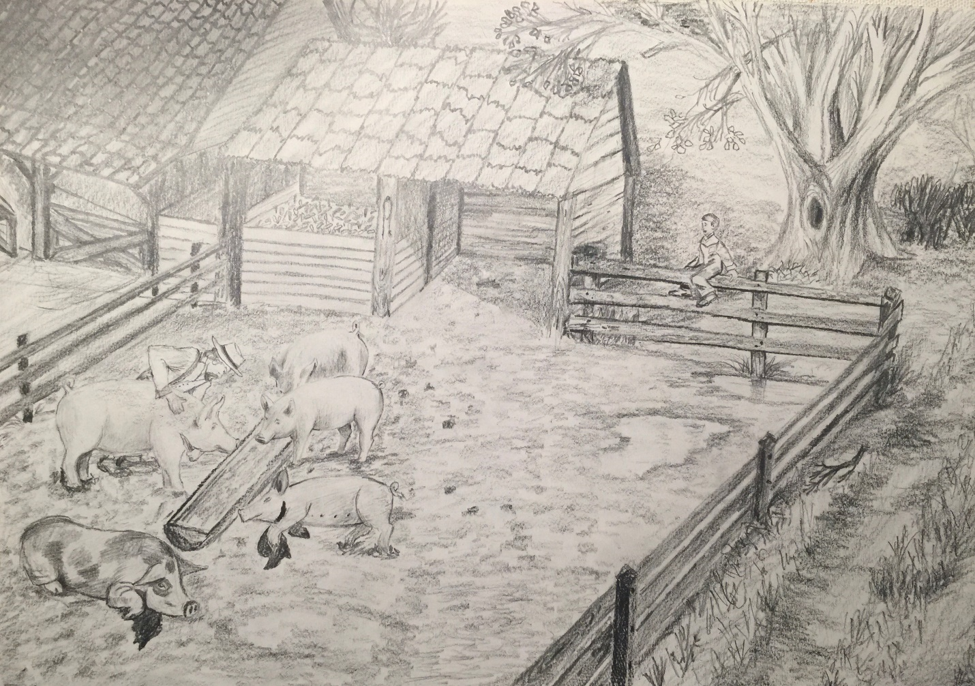

When I was a child, we often had pigs, although we never had an adequate set-up to attend to them well based on modern pig farrowing technology. In 1975, my dad and one of my Trivette cousins from Boone, erected a wire fence that led from the barn and around a good section of a stream that became our hog lot. The pigs could roam in the open field and forage in a partially wooded area and, of course, lounge in the cool water of the branch (another common word for stream or small creek, pronounced like “brainch”). At night, the pigs would sleep in our old barn.

King Phillip, a stately Yorkshire with an ever-ready smile, was lord of our herd of swine in the early days. Phillip was long, seven feet at least, and stood nearly four feet tall at the top of his back. His tail was left long and natural, but he kept it curled above his volleyball-sized bollocks. He would strut like a rooster in a hen house; indeed, he was the king of his own sow camp. At his peak, he weighed around 750lbs, enormous, even for a boar hog. He was so fat that it was easier to go around him than it was to go over. This girth led to his ultimate demise though, because he was causing injuries to the slighter sows who were unable to bear his considerable bulk.

We bought the baby boar along with eight shoats from Mr. Phillip Ollis, a professional butcher and meat inspector from Morganton. It just seemed right to name the pig after his original owner. Phillip was raised to be the potentate. We all loved him deeply and it didn’t take long to see he was bound for greatness. He loved to be petted and scratched. He would lean on my dad affectionately, and my brother Glenn and I played with him by the creek when he was smaller. He cheerfully ate the mud pies that we would diligently make for him. Yes, pigs can eat remarkable amounts of dirt. My dad said swine needed the minerals found in the soil. Phillip loved to eat weeds and we would sometimes bring giant rich weeds and lamb’s quarter to supplement his interminable appetite. He also held pumpkins and watermelons in high regard. From time to time, Phillip would “step through” the fence and get out. I say “step through” because he could have easily destroyed any section of our wobbly fences, but he and my dad had an amicable gentlemen’s agreement. He was an orderly outlaw whenever he broke out of his pasture, and his normal modus operandi was to show up at the back porch of our house where my mom usually threw out scraps for the dogs. Whenever this happened, my dad would say, “Come on Phillip, let’s get on back,” and without any shame or questioning, the two would slowly lumber back towards the barn. He was the smartest hog I ever knew.

Phillip was a special pet and while I remember his subjects and their dispositions, none of them had names and their faces are now shaded in anonymity, but certainly not Phillip. One of the most vivid scenes from my childhood was of my dad riding Phillip. Usually, these pig rodeos would begin as petting sessions during feeding time. My dad would pet Phillip and then casually saddle-up for a quick little jaunt through the mostly manure, muddy field. Depending on Phillip’s mood, my dad could stay on for quick 20-yard dashes or minute-long promenades. It was a sight to see and one I’ll never forget.

Pigs have small lungs for their size, and despite being prone to a variety of respiratory infections, they can live up to fifteen years, although most farm pigs have untimely deaths usually before they reach their third birthday. I made the drawing shown based on a tale I heard about my great-grandpa killing hogs with a knife. In my experience, most hogs slaughtered at home are shot with a .22 caliber pistol or rifle. Treated kindly, even with abundant tenderness, my great-grandpa would nestle up next to each pig and respectfully cut their throats without inducing any avoidable suffering. As the saying goes, “He killed them with their love.”

Phillip was part of the family for five or six years. My dad didn’t have the heart to eat Phillip, so we sold him to a pen hooker who took him to the auction in Hickory. A few weeks after Phillip went to the sale, my dad cruelly introduced us to Phillip #2. The insensitive naming wasn’t lost on us, but we progressively accepted the woefully inferior creature over time. Even so, the memory of the one true king and his easy-going grin endures to this day.