Daddy implored, “Joan! Did you set that alarm? I have to be out of here by at 4:30 at the latest. You know those fish won’t bite much after the sun gets up good. And I have to get out there before all those guys who don’t know what they’re doing. They’ll spook every fish in the water, and then none of them will bite.”

And Mom answered with the calmness of someone who had heard these statements far too many times. “Now, Dick, you know I have the alarm set. 3:30 should give you plenty of time.”

And Mom answered with the calmness of someone who had heard these statements far too many times. “Now, Dick, you know I have the alarm set. 3:30 should give you plenty of time.”

With that, Libby and I saw the light go out and heard the quietness of a family trying earnestly to go to sleep. Before long, we heard Daddy snoring. Libby and I dropped into unconsciousness not long after that.

We had no more closed our ours, or so it felt, when Mom came to our room, turned on the overhead light on in our eyes, and unapologetically called, “Come on, young ‘uns! Breakfast is getting cold!” We rolled out of bed and stumbled into the harsh fluorescent light bouncing off the yellow walls of the kitchen. Wiping the sleep out of our eyes, we climbed up on the stools at the bar. Daddy was already there, dressed in his hunting clothes. It wasn’t so much that our sleepy eyes saw him as our noses told us he was there. He loved those hunting clothes, and despite Mom’s insistence that they be washed, he forbade even the thought of it. He would say they were just getting good and broke in, and if they were washed, the animals’ keen sense of smell would warn them that he was there. It was when he had this camouflaged clothing on that I was glad Libby sat on the middle stool closest to him. I didn’t envy her.

As my eyes squinted open, the clock on the stove told me it was all of 4:00. Mom had gotten up at 3:30 sharp and now had our usual full breakfast on the table. She mandated that Libby and I would get up, no matter the time, and eat a good hot breakfast as a family. And so there we were, chowing down (or at least chewing and swallowing in our sleepy state) biscuits and gravy with country ham, scrambled eggs, and homemade preserves, We weren’t allowed to drink coffee yet, so we washed it all down with a big glass of milk. Orange juice was a luxury we didn’t often have.

Daddy finished long before we did and left the bar to go to the gun room to complete his fishing ensemble. When he walked back into the kitchen, he sported his fishing vest over his red flannel shirt and had his camouflaged jacket in one hand and his hip waders in the other. He had prepared his fishing creel, pole, and bait last night, so he was chomping at the bit to get out. Grabbing his cap, he slapped it on his head as he hurried out the door. We turned our heads just in time to see the door close behind him. We knew from “The First Day of Fishing Season” in years gone by that we could expect him back by around 11:00. His creel would be filled with his limit of fish (and very often several more, but we won’t talk about those!). .

Once Daddy was gone, Mom gave her attention to Libby and me. Libby’s head had dropped down, and I thought she was just about ready to let it fall into her plate. Fortunately, Mom called to her, “Lib! Pick your head up, child!” Startled, Libby jerked her head up. She looked somewhat stupefied as she tried to find her bearings. She slowly wiped a small stream of drool off her chin and sat up a little straighter. Libby never had and never would be a morning person, and I was and still am a morning person.

Now that Mom had both our attention, she lowered her voice and said, “Girls, you can go back to bed for a little while if you want to.” Libby immediately slipped off the middle stool and headed straight back to our bedroom. I was wide awake by now and stayed up with Mom. Mom never lacked for things to keep her busy on these early breakfast days. Sometimes I helped her; sometimes I studied. That morning, I studied.

The rest of that Saturday morning went as it normally would have. Mom got ready for work, we left the house at 7:30, she droppedt us off at Maw and Paw’s house, and headed on to work at Sears. We skipped down the path and into the house to watch cartoons until the dew dried off enough for us to go outside and see what mischief we could get into.

That time came about 9:30, and Maw couldn’t have been happier to get us out from under her feet. Libby and I played hide and seek, chased the chickens, and touched our feet to the worn place the apple tree branch as we swung up high in our tire swing. We giggled and played until 11:00 when true to our expectations, Daddy appeared through the opening in the tall hedge and walked down the beaten path. He carried his creel like a shoulder bag, slung over his head and onto one shoulder, the basket riding on his opposite hip. He had his pole in one hand and in the other was a string of fish that obviously contained more than the seven fish limit.

He called Paw, Libby, and me over to see the results of his morning. We hadn’t even gotten there before the bragging started. “I’d say I had a pretty good morning, wouldn’t you, Dad? Look at all the good eating strung out there. Nine of these are second or third yearers [meaning that they had amazingly survived one or two fishing seasons already]. They’re all between 13” and 17” long. That takes skill, girls. Those big ones don’t bite at just anything!” His voice got louder with every sentence, and his chest seemed to puff out as well. Daddy was in his element here, and he loved every second of it. This is what he lived for.

He called Paw, Libby, and me over to see the results of his morning. We hadn’t even gotten there before the bragging started. “I’d say I had a pretty good morning, wouldn’t you, Dad? Look at all the good eating strung out there. Nine of these are second or third yearers [meaning that they had amazingly survived one or two fishing seasons already]. They’re all between 13” and 17” long. That takes skill, girls. Those big ones don’t bite at just anything!” His voice got louder with every sentence, and his chest seemed to puff out as well. Daddy was in his element here, and he loved every second of it. This is what he lived for.

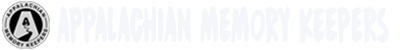

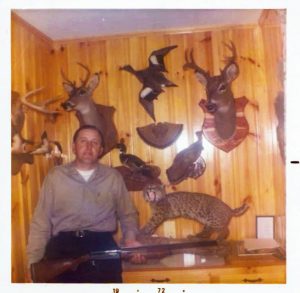

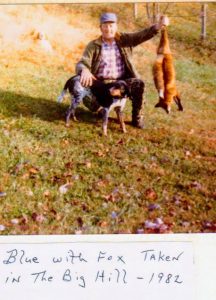

Daddy was a real outdoorsman. He was a hunter’s hunter and a fisherman’s fisher. He couldn’t wait to get out and get up into the highest peaks and the roughest country. The story you’ve just read repeated itself over more times than I care to remember. It might have been fish, or it might have been deer, turkey (our garage walls were covered with over 100 tails and beards), foxes, or bobcats. The target of the day did not matter so much as the thrill of the chase.

But even more than that, Daddy lived to get up into those unspoiled mountains where he could be alone and get away from all the worries and rigors of real life. He became one with nature and God there. He found renewal and hope and purpose there. He needed to be there as much as he needed air in his lungs and blood running through his veins. Our world would be a whole lot better off if everyone could find such a place.