I had heard from my grandmother, Blanche Dwiggins Smith, that her great-great-grandfather, Daniel Dwiggins, was a circuit-riding Methodist preacher in the early to mid-1800s, so you can imagine my excitement when I recently found the following entry in the 1850 census for him: “Daniel Dwiggins, 71, clergyman, Methodist E.” In the early days, the Methodist Church was known as the Methodist Episcopal Church, deriving that part of the name from the Anglican Church of England.

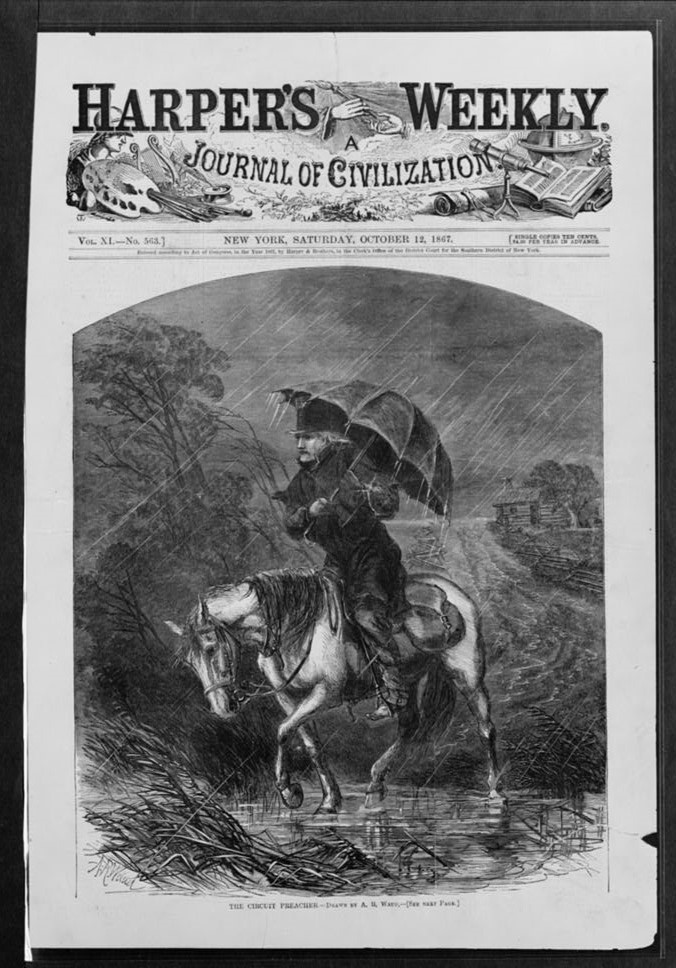

Methodism can be traced to the beliefs of John Wesley, an Anglican bishop who, with his brother Charles, came to America to preach the gospel in the mid-1700s. Eventually, their followers became known as Wesleyans. John himself ordained Francis Asbury, a preacher from England who came to America and settled in Halifax County, North Carolina. His job was to recruit itinerant preachers, called circuit riders, to go from place to place to spread the gospel. They preached to small and large groups wherever they could find listening ears, often in people’s homes, where they might have a meal and spend the night.

This background helps to explain why Daniel became a preacher. During the years of his ministry, he traveled on horseback and tried to bring souls to Jesus right here in the Piedmont. He was also instrumental in founding Center United Methodist Church, as it is now known. In 1833, after a meeting in a neighbor’s home, John Smith gave two acres of land by a deed to Daniel Dwiggins, his son, Ashley, and several other men in that area for the purpose of building a church. At first, they constructed a wooden arbor where people could worship outside. Later on, they built a church. Today, there is a newer building beside the arbor (listed in the National Register of Historic Places) and a cemetery across the road where most of my Dwiggins ancestors are buried.

During the Civil War, the Methodist Church, as did several other denominations, split into a Northern and a Southern branch. These two groups held very different views of slavery, and they stayed separate until becoming the Methodist Church USA in 1939 and finally the United Methodist Church in 1968. I have never understood how people could, if they were believers, condone slavery and participate in it.

When Daniel was not preaching, he was a farmer whose land was part of the original Daniel Boone Granville land grant, which Daniel sold earlier to his nephew John Boone. The original deeds, dated 1803, were in the possession of my grandmother, who eventually gave them to the library here for safekeeping. In any case, Daniel had a farm, and according to the slave schedules, owned over a dozen slaves. He and his wife Ursula Crews Dwiggins had five children and are buried in the Dwiggins Family Cemetery, which was part of his original property. Of his five children, his son Ashley inherited the homeplace. He was my third great-grandfather, born in 1804. When the Civil War began, two of his sons joined the Confederate Army: Daniel, and my great-grandfather, James Patterson Dwiggins. Both survived, but Daniel was never the same after the war.