Fall is in the air, and I love it. Fall has become my favorite time of the year as the earth slows down and prepares for a period of rest and renewal. I am usually ready for some rest and renewal myself. In years past, though, fall was probably the most exciting time of year for lots of us in these mountains. For with the coming of fall came the golden hue to acres and acres of burley tobacco, signaling the time for it to be cut and hung in barns to cure.

The coming of fall and the harvest of the tobacco fields had far-reaching effects. Tobacco meant Christmas for many children, and tobacco meant paying off bills that had piled up for several months. Tobacco meant buying new shoes. It meant buying things for the house or the farm that families would never have had otherwise. Burley tobacco meant cash in the cash-poor high country.

The unmistakable sweet smell of the stalks of curing leaves, hung neatly in the barn, filled our noses and sometimes stung our eyes. I ride my bicycle on a trail where there is a barn full of tobacco right now, and no matter how many times I pass by, my mind brims over with nostalgia. I often stop and just marvel at how powerfully my senses hold me there. I think I could sit right there all day long, lost in the distant past.

The unmistakable sweet smell of the stalks of curing leaves, hung neatly in the barn, filled our noses and sometimes stung our eyes. I ride my bicycle on a trail where there is a barn full of tobacco right now, and no matter how many times I pass by, my mind brims over with nostalgia. I often stop and just marvel at how powerfully my senses hold me there. I think I could sit right there all day long, lost in the distant past.

The Burley tobacco market always opened the Friday after Thanksgiving, but we never had ours ready that early. We usually started working it around the first of December, finishing sometime before Christmas. In Ashe County, December was not a timid month as it often is lower elevations. December in Ashe County was winter, and it was cold, sometimes very cold.

The tobacco lined the whole loft of the livestock barn, hanging halfway down to the floor. Old cane-bottomed chairs, often with a hole here or there in the canes, welcomed us as we climbed the stairs to start work on those cold, damp days. And the days did have to be damp or else the tobacco would not be “in-case,” meaning that without dampness in the air, the tobacco would be too dry and brittle to handle. In-case tobacco was pliable and strong, and so it was on those days we worked.

Daddy and/or Paw graded the tobacco, stripping the leaves and separating them into piles of similar quality and size. This was an important job because tobacco that had been properly graded brought more money. Poor quality leaves in high quality hands lowered the price for the high quality leaves, and high quality leaves in poor quality hands only brought low quality prices.

As Paw or Daddy graded, the rest of us tied the tobacco into hands. A well-tied hand was a beautiful sight to behold, and Maw knew how to tie the perfect one. She taught Libby and me well. First, you chose your tie leaf. That leaf was the widest and prettiest leaf you could find, and it was used to hold the stems of the hand together. Folded neatly, this tie leaf was as smooth and soft as silk.

A well-tied hand was comprised of leaves that were all approximately the same length. The tops of the stems, all lined up evenly, were clenched in the center of your palm with your fingers curled around them. More were added until the diameter of the hand was just the right size. The stems were held together very snugly so that the leaves wouldn’t fall out. Next, you took the folded tie leaf and wound it tightly around the hand. Finally, the tip of the tie leaf was pulled firmly through the middle of the hand and smoothed down to fit in with the other leaves. What you had when you finished resembled the size and shape of a large feather duster.

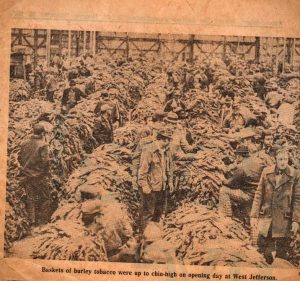

Hundreds of hands were tied in this same manner and then arranged by grade on flat baskets for market. How the hands were packed on the basket went a long way in determining the price the tobacco buyers would bid for it. Every year without fail, a few farmers tried to “nest” their less than desirable tobacco in the middle of a basket hoping it wouldn’t be noticed and the whole basket would fetch a higher price. This seldom worked; the tobacco companies trained their buyers well to watch for this sort of thing, and a tobacco buyer who missed nested tobacco too often found himself looking for another job. I know this to be true because Daddy was one of those buyers who vigilantly watched for those nested baskets.

This is all a pretty good description of how the job of working off the tobacco was done, but it doesn’t tell you anything about what it felt like, and I remember that even better than how it was done. In a word, it felt COLD. I don’t think I have ever been any colder in my entire life than I was those days in the barn working off tobacco.

By definition, the barn was drafty, and being in the loft high above the ground made it even worse. Also, the damp days we needed to work the tobacco made the cold feel even colder. We wore two pairs of socks and often two pairs of pants. Scarves and hats and heavy coats covered layers of clothing underneath. Still, we were cold. My feet would get so numb that I couldn’t feel them. My nose turned red, went numb on the end, and ran like a faucet.

By definition, the barn was drafty, and being in the loft high above the ground made it even worse. Also, the damp days we needed to work the tobacco made the cold feel even colder. We wore two pairs of socks and often two pairs of pants. Scarves and hats and heavy coats covered layers of clothing underneath. Still, we were cold. My feet would get so numb that I couldn’t feel them. My nose turned red, went numb on the end, and ran like a faucet.

But my hands may have been the worst. Because it was so important to handle the tobacco carefully, you needed to be able to move your fingers well. That meant you really couldn’t wear gloves. Bare hands got cold very quickly. And they also turned black very quickly from the tar in the tobacco. The tar was very sticky as well, so not only were my hands frozen, they also stuck together as I worked.

When we stopped for dinner (our midday meal) or finished for the day, we couldn’t wait to get to the house where the warm heat from the stove would hit us square in the face as we entered. Because we were so cold, it felt even warmer than it actually was. Maw, Libby, and I would huddle up against the stove to thaw out, and my hands and feet would actually hurt to the bone as the heat penetrated the numbness.

In spite of the cold, these were good times. We talked together and laughed together as we worked. Paw would tell stories of his rowdy youth, and Maw would sing hymns. This was a family time, and we shared our lives in that cold, drafty barn. We survived the cold weather and the sticky tar. We made up for all that by being there, as a family, together, and I wouldn’t trade those days for anything. Our hands may have been cold, but laughter and love sure did warm our hearts.