As the years pass and we grow older, we gain an appreciation for those that came before us. I know that is true for me; how I view the world today is the result of a comparison of what I know of my own history with that of my parents. One thread that has remained constant in that time is something that my Father told me when I was very young: that recognizing our individual responsibility for our own actions and welfare is the key to our American way of life. If you want something done, do it yourself—because if you wait for things to happen for you, you will be waiting a long time. I have always believed that this attitude is what separates Americans from the rest of the human world.

My Father was raised on a farm on the banks of the New River in Virginia’s Appalachian Mountains. As a kid he hunted, fished and worked with his brothers and sisters, and delighted in telling me of those childhood years and what he remembered of his family predecessors, folks who had first settled in the area before the end of the American Revolution. He demonstrated, through word and deed, his pride in those Hamptons that had come before him, those that had joined the fights in that Revolution and later the Civil War, and it was made clear to me that he expected that I would never shame their name. When the Depression worsened he decided in 1936 to join the Army, to take some of the burden off his parents; he was 18 years old.

Because of his love of horses Dad originally wanted to join the Cavalry, but by the time he had enlisted the horse soldier was obsolete. Because of his natural ability with firearms and his mathematical aptitude he was placed in the Artillery, specifically the then-new field of anti-aircraft artillery. As a hunting youngster Dad was one of those unsung artists with a shotgun, and even later in life when I began hunting with him in the mid-1960’s, it was a joy to watch him work on our grouse and quail; this natural ability easily translated into the complicated field of manipulating guns for ground-to-air combat. When the war broke out he was sent to the Pacific Theatre, and throughout that struggle he participated in many of the island campaigns, receiving battlefield promotions, and finally retired as a Lieutenant Colonel in 1958.

Because of his love of horses Dad originally wanted to join the Cavalry, but by the time he had enlisted the horse soldier was obsolete. Because of his natural ability with firearms and his mathematical aptitude he was placed in the Artillery, specifically the then-new field of anti-aircraft artillery. As a hunting youngster Dad was one of those unsung artists with a shotgun, and even later in life when I began hunting with him in the mid-1960’s, it was a joy to watch him work on our grouse and quail; this natural ability easily translated into the complicated field of manipulating guns for ground-to-air combat. When the war broke out he was sent to the Pacific Theatre, and throughout that struggle he participated in many of the island campaigns, receiving battlefield promotions, and finally retired as a Lieutenant Colonel in 1958.

Today we seem so far removed from that time of a world at war; after all, it has been over 70 years since millions of our young Americans joined that fight. It had been about that long since the end of the Civil War to the time of Dad’s enlistment and our American troops had to relearn the ‘art of war’, but the one thing our enemies had not counted on quickly became abundantly clear: that the American fighting man was willing to bring the fight to them.

As a child of course I knew that my Father had been in the Army; some of my earliest family memories are of us living in the Ocean View area of Norfolk, Virginia just before Dad’s retirement from the service. We moved from Tidewater back to the mountains of Virginia and about the time I was 8 years old I began to take notice of some of the remnants of Dad’s service years. Like so many of his generation that were involved in the war, Dad did not talk about his war experience; but two items in particular from that time held my attention and I pestered Dad with my questions about them. It wasn’t until I was in high school that I finally got answers for those questions.

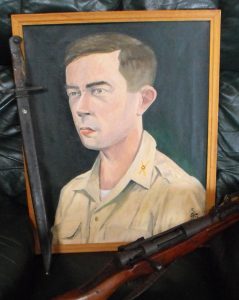

In the living room closet, alongside of Dad’s .22 rifle and 20 gauge shotgun, was a Type 99 Japanese Arisaka battle rifle, complete with bayonet and scabbard. On the gun were three places where it had been struck with bullets. As a kid I was allowed to handle this rifle, with of course close supervision, and it was an item I held in great esteem, even though most people considered it a piece of junk. Also, there was on the living room wall a crude painting, a portrait of Dad, done on a piece of canvas cut from a truck cover, a stylized picture with oriental features. I wondered why he would keep such a thing in such a place of prominence in our home. Late one night I found out.

Mother was working the night shift at our small-town local hospital (she was an RN) and my sister was away at college when I woke to the sound of my father shouting from his bedroom. I quickly ran to see what was the matter and found him sitting on the edge of the bed, awakened from what had to be a bad dream. After he regained his composure, there in the glow of his reading light, he took me to Okinawa in April, May and June of 1945. It was the only time in his life that he ever talked to me about the war, of what he did and what he saw; and he told me that he wasn’t afraid of going to hell when he died because he had already spent 82 days there.

Mother was working the night shift at our small-town local hospital (she was an RN) and my sister was away at college when I woke to the sound of my father shouting from his bedroom. I quickly ran to see what was the matter and found him sitting on the edge of the bed, awakened from what had to be a bad dream. After he regained his composure, there in the glow of his reading light, he took me to Okinawa in April, May and June of 1945. It was the only time in his life that he ever talked to me about the war, of what he did and what he saw; and he told me that he wasn’t afraid of going to hell when he died because he had already spent 82 days there.

Near the end of the battle, over the course of three days Dad was ordered to interview, through an interpreter, one of the few captured Japanese officers, and at the end of the interview before the officer was led away, Dad gave the man two packs of cigarettes. Unknown to Dad, once he was back in the makeshift holding area for prisoners that officer asked for a piece of canvas, and from memory he painted Dad’s portrait. Two days later this officer committed suicide. After Dad was given the painting and the news of the suicide, he walked the ground near the airfield and found the Japanese rifle. He told me he had kept these two things to always remind himself of what home and family really meant, and to one day perhaps give them, and his story, to his children.

I have many memories of my Father, some good and some not; but I have always held on to that picture in my mind of a 27-year-old mountain boy, standing on that black sand under the burning tropical sun, holding that rifle, with the rolled-up canvas painting under his arm. I would very much like to have known him then.

Thank you, Dad, for everything.