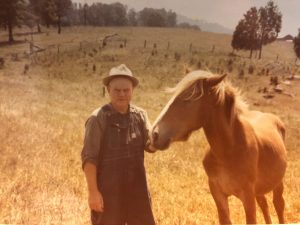

I can’t look at a pair of Pointer Brand overalls without thinking of my Granddaddy. He wore a pair of those overalls—made in Bristol, Tennessee, by L.C. King Manufacturing Co.— just about every day that I knew him (exceptions being at my grandmother’s funeral as well as his own).

I can’t look at a pair of Pointer Brand overalls without thinking of my Granddaddy. He wore a pair of those overalls—made in Bristol, Tennessee, by L.C. King Manufacturing Co.— just about every day that I knew him (exceptions being at my grandmother’s funeral as well as his own).

My mother’s father, Cargille Charles Hale, was born in 1907, the third child of Jerry Mark and Cora Adams Hale of Washington County, Tennessee. His older brother, Hobert, 10 years his senior, was disabled from birth and never married. He had a sister, Nona Mae, born in 1900, who, sadly, lived less than five months. A younger brother, Clarence, joined the family in 1912.

The story goes that Granddaddy was named after Charley Cargille Studio, a well-known photography studio in Johnson City. Granddaddy grew up on his family’s farm in Gray Station and eventually purchased land nearby to farm on his own. He married Nina Mae Keys, my grandmother and the love of his life, and they had only one child, my mother, Clara Mae, born while the world was at war in November of 1943. Granddaddy built a little white farmhouse on the property where my mother grew up and where my siblings and I spent many summer days running hither and yon, getting lost in the corn stalks and learning the art of front-porch sittin’.

About nine or 10 years ago, when Mom was visiting us in Atlanta, I got to asking her questions about my grandparents and our family history. It was very informal—she was relaxing in the living room, and I typed up her very candid answers as she spoke. (I highly recommend that everyone do something similar with your loved ones, as I treasure these interviews, especially since Mom passed away in 2012.)

Mom had a loving relationship with her parents—she loved them both dearly but was a bit of a daddy’s girl. Not much for housework or other domestic duties, she loved being outdoors and helping her dad on the family farm. And he helped her with her schoolwork. While he didn’t have a high school education, Granddaddy was extremely smart and sharp as a tack.

“I had trouble with the written problems, but my dad was so smart in math, he could do it in his head. He didn’t need a pencil or paper …” Mom said. “I hated math, and I hated written problems, especially. But I always got my homework because he helped me with it.”

And it paid off—or rubbed off, as Mom ended up as valedictorian of her high school class. Granddaddy’s very strong work ethic is another trait that he passed on to my mother. An early-to-bed-and-early-to-rise man, he took his farm work very seriously, and he seemed content to stay there. Other than driving to the co-op in Jonesborough to get farming supplies, it was rare for him to go far from home, Mom said, adding that he didn’t accompany her and Grandmother on their Saturday-morning trips to town (Johnson City) or to the Methodist church on Sundays.

And it paid off—or rubbed off, as Mom ended up as valedictorian of her high school class. Granddaddy’s very strong work ethic is another trait that he passed on to my mother. An early-to-bed-and-early-to-rise man, he took his farm work very seriously, and he seemed content to stay there. Other than driving to the co-op in Jonesborough to get farming supplies, it was rare for him to go far from home, Mom said, adding that he didn’t accompany her and Grandmother on their Saturday-morning trips to town (Johnson City) or to the Methodist church on Sundays.

Granddaddy was a very private person—but he seemed to be well-known and well-liked in the community. I remember all kinds of people waving to him as they drove by the house—and sometimes, after seeing that he was outside, people would pull in the gravel driveway for an impromptu visit. While he was not a professional barber, he regularly cut men’s hair with his clippers for a fraction of the cost—next to nothing, really—of a regular haircut. These haircuts would take place either outside or in the detached garage by the house.

His talents and abilities didn’t stop there. He was an excellent shot and winning turkey shoots was not uncommon for him. I’m not sure how this worked exactly, but I remember Mom telling me that men would pay Granddaddy to shoot for them, too. He also slaughtered hogs for others.

“People didn’t know how or didn’t want to kill their own hogs, and they would get him to do it,” Mom said. “I guess he went to their house to get them, and he shot them and hauled them in the back of the truck.”

When he got back to the house, Granddaddy went to work.

“They had a great big old thing that they dipped the hog in after it was dead but before they hung it up by its feet,” Mom said. “It was hot, and it got the hairs off. It sat on the ground, and it was great old big and round. They put hot water in it. It was black.”

Mom continued to explain the butchering process.

“Then he would take the hog down and cut it into parts—ham, shoulder and in the middle of it was what you make bacon out of. … We’d make sausage out of parts of it; they had a sausage grinder.

“Then he would take the hog down and cut it into parts—ham, shoulder and in the middle of it was what you make bacon out of. … We’d make sausage out of parts of it; they had a sausage grinder.

“They would wrap the pieces—the hams, shoulders, the middlin’, tenderloin—and put salt on them and hang them in the smokehouse. That cured them, and they stayed all winter there. My mom would can certain parts they wanted.”

While he was nothing but a kind and gentle grandfather to my siblings and me—his only grandchildren—he apparently did have a bit of a stubborn streak.

“My dad would get mad at something,” Mom said. “And he would go up to a week at a time without even speaking. … It just took him that long to get over it.”

When I asked her what would upset him enough to render him speechless, she couldn’t recall specifics. “I don’t remember now,” she said, “could be something about the cows or something that went wrong on the farm … tractor might have tore up. I don’t remember; it’s been too long.”

One thing she did remember, of all things, is his fondness for beets—or lack thereof, actually.

“My dad didn’t like beets,” she said. “They had to be removed from the table before he would sit down there. He couldn’t even stand to be close enough to them that they sat on the table.”

Granddaddy also had quite a sense of humor.

“One time he played a trick on me,” Mom said. “He sent me to the chicken house to get something, and there really wasn’t nothing to get. He had caught a polecat and dragged the trap in the path that I would go to the chicken house. The polecat was still alive and caught by, I think, his foot.

“He knew I’d see that, and it would scare me—and it did! I came running back, hollering. Needless to say, I didn’t go on to the chicken house. I ran back home.”

Mom also mentioned a neighbor whose wife used to wear red shorts, which Granddaddy apparently found humorous. “Dad used to make fun of that—her and her red shorts,” she said with a smile. “I never saw my mother wear shorts, ever. Ever. Or pants. She always wore a dress.

“And my dad always wore Pointer Brand overalls.”