New Appalachian Moments Blog Post by Scott Ballard

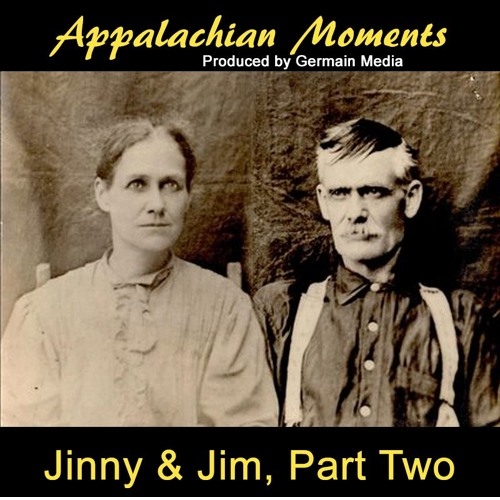

We sat a spell with Jinny in our last Appalachian Moments post, but today we get to know her beloved husband Jim, my great-great Grandfather and a prime example of the generational transition from his subsistence farming to a new way of life.

When he died, the preacher in the meeting house that Jim helped build said he was the finest man in Union County Georgia. One of nine kids, he took over the family farm and helped raise seven boys of his own with Jinny. While tales from relatives of fertile land in Texas, gold mining in Colorado or herding opportunities in Washington State always made Jim restless for a few days, his roots were sunk too deep in that Georgia soil.

Jim, like many of his era, was a subsistence farmer, growing most of what the family needed, but when the crops were good, he and the boys would often do day trips to more populated areas to peddle beans, potatoes, corn and molasses from the back of his wagon. He found a ready clientele, but this Georgia plough boy was no match for sharp-eyed housewives and did not like to haggle, often quickly agreeing to a cheaper price.

Jim did manage the farm well however, living within his means, and never carried debt past one year. And while those seven country boys went barefoot six months of the year, they had plenty to eat, except for flour bread as it was an extravagance to have a white biscuit on a Sunday morning.

As neighbors looked out for neighbors, Jim never locked his front door…all it had was a simple latch anyway…The only thing he ever asked Jinny as they rode off to church was, “Did you remember to SHUT the door? (to keep the livestock out!).”4

The family story is that Jim said of my great-grandfather, “Robert will never make a farmer, we’re going to have to educate him!” That gentle put-down changed the course of my family forever!

Jim was not a man to show his feelings, but his heart was as tender as a child’s. When my great-grandfather was preparing to leave the farm AND that way of life to attend the newly founded Lincoln Memorial University, Jim was having second thoughts, and rode out a quarter mile to the last gate on the farm.

Jim got off his horse and after kicking the dry dirt in the road for a moment, said, “Robert, if you leave now, you will never come home again. I think you are too young to leave us. And, if you’ll agree to stay, I will find the money to pay your board at a school closer to home. We’ll make out somehow. We always do. I want you to stay.”

My great grandfather looked down at this slightly built but straight-shouldered man and knew his words were true; his father would sacrifice anything to keep his sons nearby. But in the silence that followed my great grandfather could not say what Jim wanted to hear…his mind was already building a new life off of the farm and away from those red clay hills. After a short silence and a nod goodbye, Robert’s brother flicked the reins and the horses pulled away to the train station.

Years later, my great grandfather did return for a visit as Jim was dying, and in his crisp new World War I Army uniform he leaned over Jim’s bed and pulled him tight for the only embrace he ever had with his father.

Jim said there was no need to go to any expense for a tombstone, adding that a good-sized old creek rock would do. “Just cut my name on it” he said, and that will be alright.

That old creek rock is still there in the pines and even though the simple epitaph has long since weathered away, the memories of fathers and sons linger on. (his boys and their families put up a formal tombstone to honor both Jinny and Jim many years later).

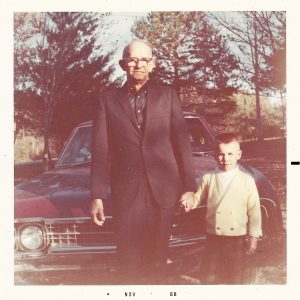

Add-on: I had expressed a desire to my mother to go to visit Lower Young Cane, Georgia, and find the old farm, when she produced some pictures. Two of my great-uncles took me there as a small boy…so I guess I have to rephrase it, I want to go BACK! (photo at right Scott Ballard with Great Uncle Otis Kincaid)