New Appalachian Moments blog post by Scott Ballard

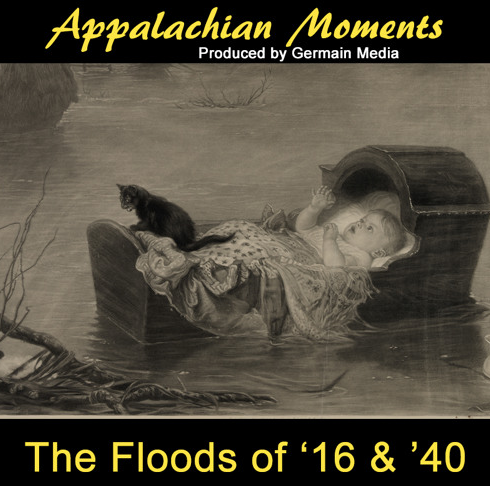

Many people can recall various floods or high water, but very few residents remember two earlier events of epic proportions that devastated our region. That’s because the flooding that truly overwhelmed many of our ancestors occurred in 1916 and 1940.

By the early 1900s, railroads had forged their way into the mountains of North Carolina. Nothing seemed to be able to slow the rapid progress by even the most remote communities. Nothing, that is, except Mother Nature.

In 1916, over 10 days, two hurricanes, one from the Gulf of Mexico, and one from the Atlantic broke all records for rainfall. In fact, over 22 inches of rain fell in one day at Altapass near Grandfather Mountain, at the time it was the greatest total ever recorded, anywhere in the entire US!

And for unexplained reasons after the 1916 flood, development increased again within those same river basins of many Appalachian communities.

Just 24 years later, in 1940, lightning, or in this case a pair of hurricanes struck again. Swollen streams and rivers jumped their banks and in their fury took with them whatever they could.

At Shulls Mill, Tweetsie Railroad’s Old Number 9 locomotive engine waded through 2 feet of water and passed a timbered Grandfather Mountain where it looked like the entire mountainside was a giant waterfall. But as the engineer was backing up another washout stranded the train with nowhere to go. Train service never again made it to Boone.

Down in Jackson County North Carolina the scene was surreal…Ancient hemlocks floated downstream, roots first. Dead livestock rolled by and a large rooster standing on the top of a barn, crowed constantly as the barn surged around bends in the river. In one example of the flight to safety, eight family members held hands as they walked to higher ground, while feeling the road pavement giving way beneath their feet. They were the lucky ones.

In one heartbreaking account, a pregnant woman was torn from her husband’s arms as their house lifted up off of its foundation. When daylight next appeared everything was gone…except the pie safe…they found it standing upright in a nearby field with the leftover food from supper still in it.

The floods of 1916 and 1940 left in their wake shattered lives and unimaginable devastation. The memories have endured for many generations and have become a permanent part of our mountain heritage and given life to the expression—“I’ll be there, Lord willin’ and if the creek don’t rise.”