A hundred years ago, it was bad news if you received a letter with black on the edges…join us on Appalachian Moments and we’ll discover why!

Families back when experienced death more often. What do you think that means and why? Several reasons, first, families were much bigger and childhood diseases such as the measles or even chicken pox could be fatal. Also it was common to have three generations under one roof. The reality of aging and death could not be sequestered away from view in some remote nursing home or hospital.

In the days before embalming it was imperative that far flung family members were notified quickly if there was a death. And thus, the original version of priority mail was born. If a postmaster received a letter with black marked edges, they forwarded it to its destination with utmost haste, even personally delivering it if necessary.

Most families tried to keep the body for three days before burial to follow the ritual of Jesus’ death, burial and resurrection, and to allow family members to come home, but hot and humid summer weather didn’t always cooperate!

In the winter months it was just the opposite. If the ground was frozen and there was no dynamite available, the corpse was placed in a protected place, most often a barn, until the Spring thaw. In one of our many interviews, one person recounted that dynamite charges were still being set off during the funeral service!

The six-foot depth of the graves can be traced back to an original decree from the Mayor of London, England during an outbreak of the plague in the 1660s. He deemed that six feet was deep enough to avoid further infections (there was no guidance from the CDC).

A colorful local legend around the mountains was that when a specific small tree came into bloom it was a sign that the ground had softened enough for those circuit riding preachers to resume conducting delayed burial services. The name of that small tree: The Serviceberry, Coincidence? You decide!

During graveside services, the family and friends would stay until the grave had been completely filled in, one shovel-full at a time. The preaching was finished but what to do during that possibly awkward time? Why, sing of course!

You’ve heard of wedding singers, but there were also funeral singers. These folks stopped whatever they were doing at anytime, anywhere to sing at a funeral.

Occasionally the undertaker might give them a few dollars and that was just a bonus, as most funeral singers back then never asked for compensation. It wasn’t about the money. If a pastor could preach the deceased to Glory, then the singers could do their part too.

Oft repeated songs included Going Down the Valley One by One, In the Garden, We’ll Never Grow Old, Heaven Holds onto Me, Nearer My God to Thee, Each Step I Take, Will the Circle be Unbroken and of course, Precious Memories.

… how they linger

How they ever flood my soul

In the stillness of the midnight

Precious, sacred scenes unfold

Church Street Childhood By Linda H. Barnette

When I was growing up on Church Street several decades ago, life was very different than it is now. Everything revolved around family, friends, and church. All of the neighbors were close and helped each other out. Daddy and several of the men on the street shared the produce from their gardens with a lot of other people. The rule was that vegetables were free but you had to pick your own! Everybody looked out for everybody else, and those times were sweet and innocent, as I recall them. In the evenings, everybody was outside either visiting or just resting.

Even though our neighborhood was in town, it was also like a farm in some ways. My Grandfather Smith had a barn and several outbuildings, including a granary. He and my dad raised chickens and pigs, corn, and other vegetables. I don’t remember the cows, but there must have been some, or else they wouldn’t have needed the barn. I distinctly recall the pigs that Daddy kept in a fenced lot in our back yard. On occasion, they would get out and chase the kids. I was petrified of them. In fact, the only animal that I loved then was my dog. I also had one sweet kitty, named Peanut Butter, whose life I desperately tried to save after she was injured in an accident.

As I have mentioned before, my cousins and I rode our bicycles on the street, never giving a thought to speeding drivers as there are today. The street ended three houses below ours, so the only people who drove on it were the people who lived here. Not only did we ride our bikes in the street, but we also learned to roller skate on the sidewalk at First Methodist Church. We were never concerned about strangers and never locked our doors until one summer night when a stranger ran through our yard during Masonic Picnic week. After that incident, we always locked our doors.

My favorite possession as a child, if you can call it that, was my playhouse. The building was about 8 feet by 12 feet, perhaps larger, was originally one of my great-grandfather’s chicken houses, and sat on the spot where I live now. Daddy painted the outside and fixed up the inside, even adding a bar and a cabinet. He put a desk and chair in it and also a mirror and an old stove that had been a gift from the overseer at Boxwood when I was a child. I had tea sets and old clothes that had belonged to family members. It was a very nice place after he fixed it up and much better than being stuck in the house. My next-door neighbor and lifelong friend, Dianne, and I used to hang out there a lot.

What good memories! Writing this series brings me much pleasure, and I hope you are enjoying it. There is more to come.

Albert Hash

We pay a literary tribute to a musical legend of the High Country of NC.

The phrase “pay it forward” might be a bit overused these days, but no one exemplifies it better than Albert Hash of Grayson County, Virginia who paid forward his love of mountain music.

In 1917, near the border of North Carolina, Hash was born into a hard life, and as a friend stated: it was root hog or die, which is an old-time saying for you’re on your own, and you had better be self-sufficient.

Hash grew up in a house full of music and he carved his first fiddle with a pocket knife at age 10. He would keep the pocket knife handy for carving, but his fiddle-making would vastly improve as the years went on.

The old adage that there is a fiddle player up each holler in the mountains applied to Hash. He got together with family and friends to play house parties, dances, and box suppers.

He sold his first fiddle for six dollars and also found that he could barter or trade his fiddles for other things. When he had appendicitis, a local preacher paid his hospital bill and Hash paid him back with a fiddle.

When his second daughter was born, he paid her hospital bill with a fiddle as well. He always playfully teased his daughter that he traded a beautiful blond fiddle with an Indian head on the scroll and lots of inlays for such a scrawny little runt of a child.

Later, when that very same daughter learned the craft of fiddle making from her father, she gave him her first fiddle…he said he’d rather have that handmade fiddle than a brand new Cadillac! A good thing too, there was no money for a fancy new car!

His fiddles made it to the big time via fellow Virginian Harold Hensley, who played Albert’s fiddles on the Hometown Jamboree TV show that featured guests like Johnny Cash, Tennessee Ernie Ford, and Tex Ritter among others. Hensley would always send Hash a post card to let him know where he’d be playing his Albert Hash fiddle next!

During World War II Hash wanted to join the Army but a heart murmur stopped him from serving. He did find work at a torpedo factory before returning to the hills of Northwest North Carolina. He farmed and made fiddles until he got a job as a machinist in a local factory.

On the top of the fiddle or scroll Hash carved various birds, like eagles, people, animal claws and even dogs. The backs of his fiddles showcased carvings of flowers and birds among other things.

While his talents were showcased for the 1982 World’s Fair in Knoxville, Tennessee and the Smithsonian Institute, his true legacy is the people he inspired to continue the tradition of old time music.

As our friend Dave Tabler says, Albert Hash ain’t a bit shy with a fiddle, he also didn’t hesitate to encourage fiddle players and fiddle makers. Coming from an era when trade secrets were hoarded like gold, Hash freely shared his knowledge. Those countless musicians have paid that kindness forward in memory and honor of Hash.

If the wind through the pines on Whitetop mountain sounds vaguely of fiddle music, it is most likely the mountain’s way of paying tribute to this fine country gentleman…Albert Hash.

Church Street Neighbors By Linda H. Barnette

Although I knew all the neighbors at least by sight, only a few of them were close friends of my parents. The Wall family, including Claire, James Wall, and his wife Esther, and Tommy and Lois Shore were our best friends and neighbors on the street.

All of the Walls were teachers, and both Miss Claire Wall and Mr. James Wall were among my favorites. Mrs. Wall was also a teacher, but her field was elementary education, and I was never in her class. Miss Wall was a lovely lady with an ever-present smile. She was my ninth grade English teacher for the last year that we were at the old Mocksville High School. Because of her, I learned to love classic literature, although I was always an avid reader. Burned into my memory is our principal, Mr. Farthing, reading Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Raven” in his deep, dramatic voice! When Miss Wall got married after her mother had passed away, my parents took her and her fiancée to Staley’s Steakhouse in Winston. I knew by that gesture how important she was to our family because we never went to dinner at places like that!

Mr. James Wall was my homeroom teacher in the eighth grade and also my history teacher at Davie County High School. A teacher from the old school, he was strict and all about the business of teaching us his subject. There was no misbehaving in his classes, probably because nobody wanted to risk getting punished, but also because that was the norm in those days. I clearly recall walking into class one day and seeing a note on the board that his wife had had a baby girl. There was no discussion about it, no cake, no party. He was a well-respected teacher, well-prepared with a master’s degree from Chapel Hill, brilliant enough to have taught on the university level, but his choice was his hometown. He encouraged my interest in history and later became the Davie County historian and wrote a book about our county. My autographed copy remains a treasured possession.

Mrs. Wall was not so much a part of my childhood, but in later years when my mother was a shut-in, Mrs. Wall was a faithful visitor who often brought Mother sweet treats. She was all about the business of hospitality. When she passed away recently, that was brought out in her eulogy.

Tommy and Lois Shore were our neighbors on the left side. Tommy was the supervisor of maintenance at the school bus garage, and Lois worked at one of the banks. Tommy and my dad often met for conversation while they cut the grass on their riding mowers.

What my dad, Mr. Wall, and Tommy Shore had in common was their love of gardening. They all three had large gardens and would meet in the evenings outside during the summer months. I can truthfully say that it would be difficult if not impossible to find three finer gentlemen than these men. They were good people, good friends, and good neighbors. For years after my dad died, Tommy Shore cut my mother’s grass and often dropped by to check on her.

I treasure the memories of those people and those days on Church Street.

My Other Church Street Family By Linda H. Barnette

My parents were Gilmer James and Louise Smith Hartley. Everyone called my dad “Slick.” How I wish I had found out where that came from! In any case, I remember that Mother and I debated whether to put his nickname on his tombstone when he died in 1985, and I’m happy to say that we decided to do that. Daddy was tall and thin with blue eyes and sandy hair much like his own father, and I inherited his coloring and height. He was witty and intelligent and was a proud graduate of the Cooleemee High School class of 1931. Thanks to Thelma Mauldin, a classmate of his, I have a copy of his graduation picture! He lived off Cherry Hill Road and drove a bus to school—no easy task in those days before roads were paved—but he made a little money that way. At various times, he worked at the mill, at my grandfather’s Esso station uptown, and for Grady Ward’s Pure Oil Company; however, his best job came about when Ingersoll-Rand moved from New York to Mocksville. For the first time, he had benefits such as health insurance and a retirement pension plan, which helped out the family more than they might have imagined. His love of gardening and public service as well as his Christian beliefs defined him as one who loved others and who wanted to help people. In a time when racism was common, he was an uncommon man. He was also gifted with numbers and always had time to help me with my high school math homework. I think he realized that he had a dreamer for a daughter!

Mother was also tall, thin, and very lovely. She had light brown hair and beautiful green eyes. She and Daddy were married in 1936 and rented a house here on Church Street until they built the house where I grew up. The lot that the house was built on belonged to my great-grandfather, so the family on this street continued. She absolutely loved shopping, and I recall many trips to Salisbury with her on her days off from work. It was such a treat to have lunch at the fountain at Woolworth’s. She was also a gifted seamstress who made my clothes until I was in high school. I remember being shocked to find out that she made the fancy little dresses for my Christmas dolls. Her first job was at Christine’s Gift Shop uptown and then at Daniel Furniture Company until a fall caused her to become disabled at age 59. Never interested in public life, she nevertheless supported my father’s ventures into politics and in other leadership roles. He proudly served 14 years on the Mocksville Town Board and as president of the Lion’s Club and also as the treasurer of First Baptist Church for over 30 years. They really were a union of opposites; she was quiet and shy, and he was outgoing and friendly. I am a perfect combination of the two of them; quiet and shy but also devoted to public service and to the good of all.

When I was growing up, I was expected to practice the piano and to make good grades in school! Obviously, I realize now that both of them had as their main goal in life to send me to college, probably because they neither one had that advantage. They never asked me what I wanted to do, and I would not have challenged them anyway. I hope that they knew how much I appreciate all that they did for me, and I do know that they were very proud when I decided to become a teacher. Much of my genealogical work is done in their honor as they both loved family above all except God.

My mother’s uncle, Marsh Dwiggins, and his wife, Belle, also lived on Church Street. I honestly don’t have memories of them, but I have a lot of memories of my aunt and uncle, Katherine and Jim Poole, and my cousin Vivian. Jim was a superb cook, and Katherine worked at Sanford’s Store and then at B. C. Moore’s. Not long ago, an older lady whom I did not know asked me if I used to work at Moore’s, and I told her that that lady was my aunt. Vivian was the cousin I grew up with, and I remember many happy hours spent in the front porch swing at the Smiths’ house.

Thank God for memories. They are the stuff that dreams are made of!

Over the Top with the 80th, Pt. 3

In this final episode of the three-part series, “Over the Top with the 80th,” private Rush Young watches from the front lines as World War I intensifies, and the Allies finally begin to push back, but how is this North Carolina mountain boy going to make it through?

Young was one of over one million U.S. Army soldiers in the Argonne Forest offensive, the largest and second-deadliest battle of the entire war.

As Young and his fellow soldiers leapt from trench to shell hole and from one boundary of trees to the next, they sometimes got ahead of their supply chain and artillery support. But the upside of having heard the constant shelling, both night and day, is that they could tell directions by listening to the sounds of the shells flying over their heads.

Along with what they called German whiz bangs, some of the enemy’s shells made an ominous, “you, you, you, you” sound as they whistled through the air!

The fields and roads looked like honeycombs from all the bombing. More unbearable even than the lean rations, the green blow flies, and the brazen trench rats were the cries of the wounded, “I’m hit, I’m hit, for God sakes please help me!” and the wild screams of the shell-shocked who were going mad from the constant explosions.

During a short break from the front lines, Young said his unit looked like train tramps, with bloody, ragged uniforms, hobbling to the rear just like those battle-hardened Brits they saw when they first arrived.

New troops taunted these shell-shocked fellas, “You call yourself American soldiers? Just wait ‘til we get to the front, we’ll show you how to fight!” Young and his mates just laughed and said, “Keep marching boys…you’ll find what you’re looking for, the Huns are waiting for you.”

Just a week before the Armistice or end of the war, Young took a devastating shot to the lower leg from a machine gun nest 1,000 yards away. After crawling 50 yards to cover and a quick field dressing of the wound he was told to lie in a ditch for safety, which he did for the rest of the day.

He was still a mile away from the first aid station and as he was being carried back, the orderlies dumped him on the ground and dove for cover every time a plane flew over!

In camp hospital #33, which Young described as floating in a sea of mud, his leg was surgically repaired but he caught diphtheria, a bacterial infection you never hear of anymore because of effective vaccines, but he survived that and 2 months later was on a boat for New York.

As he watched the French shoreline slowly fade, the lump in his throat wouldn’t go away. Instead of thinking of the joy of returning home to America and his home in the mountains of North Carolina, all he could think of were all of his friends, friends that he was leaving behind, friends who would never come home.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this personal look inside an Appalachian boy’s experiences in the First World War!

Over the Top with the 80th, Pt. 2

In this second of a three part series called “Over the Top with the 80th” Ashe County, NC private Rush Young finally reaches France to fight the Germans in World War I, but discovers that he’ll have other battles before he reaches the front line trenches.

Fresh-faced and ready to fight, Young and his friends were shocked as they witnessed a company of shot up and battle weary British troops returning from the front lines, with ragged uniforms and 1,000-yard stares.

These mountain boys were also introduced to what they called, “The Cooties” from some of these battle-weary soldiers. Cooties was another name for lice. They would battle these tiny enemies during the rest of their stay in country.

These Blue Ridge boys also didn’t mix well with the snooty Londoners from the British forces. The Brits would say, “My dear lad, you do not speak proper English!” To which Young and his compatriots would respond, “Hell no we don’t speak English, we speak United States!” Fists flew between the hillbillies and the Limeys.

The Brits had imported Chinese laborers to dig their trenches and one night a German bomb struck the Chinese worker encampment killing several. The next morning several Chinese broke into the compound holding German prisoners of war and exacted their revenge man for man.

A month later Young and his fellow troops experienced their first direct artillery shell attack or what they called the Germans delivering “iron rations.” Their faces went beet red and they wondered if they would be blown to bits before they ever faced the enemy that they had traveled 3,000 miles to fight.

As they headed to battle a message from the high command rallied their spirits. The note stated: “No enemy can withstand the 80th Division. Go at them with a yell and regardless of obstacles or fatigue, accomplish your mission. Make the enemy know that the 80th Division is here. Make them understand that resistance is useless.”

As they dug in, Young said that never had the ground and dirt meant so much to him as they pressed their bodies into Mother Earth’s shell-scarred bosom, their only friend and protector.

A 21 mile march with his pack and a rifle did wonders for Young’s appetite! The boiled beans, sow belly and slumgullion (or watered down stew) was a gourmet treat!

Traveling through many small French towns for days on end, Young mentioned he never saw a funeral. “These old French farmers apparently never die. They just get their jug of wine and black bread and work in the fields all day, every day.”

One night early on, Young was at his machine gun post and he was overcome with melancholy as the soft moonlight and stars illuminated the no-man’s land between the German and Allied forces. He said, “God commanded us not to kill so I wonder at Judgement day who will pay? Us or the people who started this war?

As the acidic smoke from the big artillery guns put a bitter taste in their mouths, Young prayed. Not for himself, but for his Division because he knew that many of them were on the brink of eternity. He often repeated the Bible’s 23rd Psalm, “…Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me…” because Young could think of nothing more fitting.

In the final episode of Over the Top with the 80th, World War I escalates toward the finale but Young doesn’t emerge unscathed…please like, comment and share your memories in the section below, thanks again for reading Appalachian Moments!

Over the Top with the 80th, Pt. 1

Today in Appalachian Moments, we celebrate the end of World War I (November 2018) by reliving a fascinating first-hand account of a farm boy from Ashe County, North Carolina in our 3-part series “Over the Top with the 80th.”

Rush Young, who was raised in Grassy Creek, NC, was 23 years old when America entered World War I and he soon found himself at Camp Lee, Virginia. He had no idea what he was getting into, nor could he imagine writing a book “Over the Top with the 80th by a buck private” which detailed his adventures!

Trumpet reveille replaced the warm chime of a mantle clock, and he went from feather beds to naked bed springs, from handmade quilts to one thin wool blanket per soldier in an unheated barracks. Lads like Young went from Momma’s homemade buckwheat pancakes, fresh butter and honey to overcooked and unrecognizable mush and fried horse meat.

Speaking of that exotic fare, at first, the garbage cans at the mess hall would be filled with this inedible Army fare, until guards were posted at each can forbidding the tossing away of uneaten food!

There were not enough uniforms ready so the first recruits were drilled in their overalls and brogan shoes for two weeks! The grounds at Camp Lee weren’t ready either and had to be cleared of planted corn and stumps. They made double time in clearing because in less than a year 50,000 troops would be there.

Young made special note that boys from the North and South were back together in an Army even though memories of the Civil War were still fresh, but where did these troops first march in front of the public? Richmond, Virginia, the original Confederate capitol. And as they marched down Monument Avenue, Young reported that they saluted a statue of Jefferson Davis!

From North and South, the Army was a great equalizer as farmers, lawyers, school teachers and doctors all became rookies. Many of the fresh faces had never seen a needle before and several fainted dead away while standing in line for inoculations, not a good start for a lean, mean fighting machine.

Young’s sweet naivete was showing when he first heard, and was appalled by, the marching song that goes, “You’re in the Army now, you’re not behind the plow, you’ll never get rich, you…SOB, you’re in the Army now!” He said, and I quote, “Gee whiz that song was terrible, but there was one worse called ‘Lulu.’” Dear readers, you’ll have to look that one up for yourself.

Six months of training and this North Carolina mountain boy was on a train to New York City and then a transport ship for a 12-day crossing of the Atlantic. Just before the ship made port in France, several soldiers were on deck exclaiming, “Look fellas, it’s a whale breaching the surface.” Surprise turned to dread when they recognized a German U-boat! The four escort Destroyers chased the submarine away.

The first thing the soldiers went for upon reaching terra firma was fresh water, but not to drink! Why? After nearly two weeks of cold salt water showers, their skin was both sticky and dry and their hair, as Young described it, was a stiff as hog bristles.

In the next episode of Over the Top with the 80th, Young finds that his first battles won’t be with the Germans, please like, comment and share your thoughts in the section below, thanks again for reading Appalachian Moments!

Is it sorghum or is it molasses?

In this edition of Appalachian Moments, and in the Fall of the year, we have a tasty test to determine how Southern you are, all you have to do is answer a simple question, stay tuned.

This question is a bit more involved than the you say ‘potato, I say pototo’ kind of deal.

Is it sorghum or is it molasses? Folks “of a certain age” in the South know that sorghum comes from sorghum cane and molasses comes from sugar cane.

Over time the two words have been combined or even become interchangeable…sorghum, molasses or sorghum-molasses.

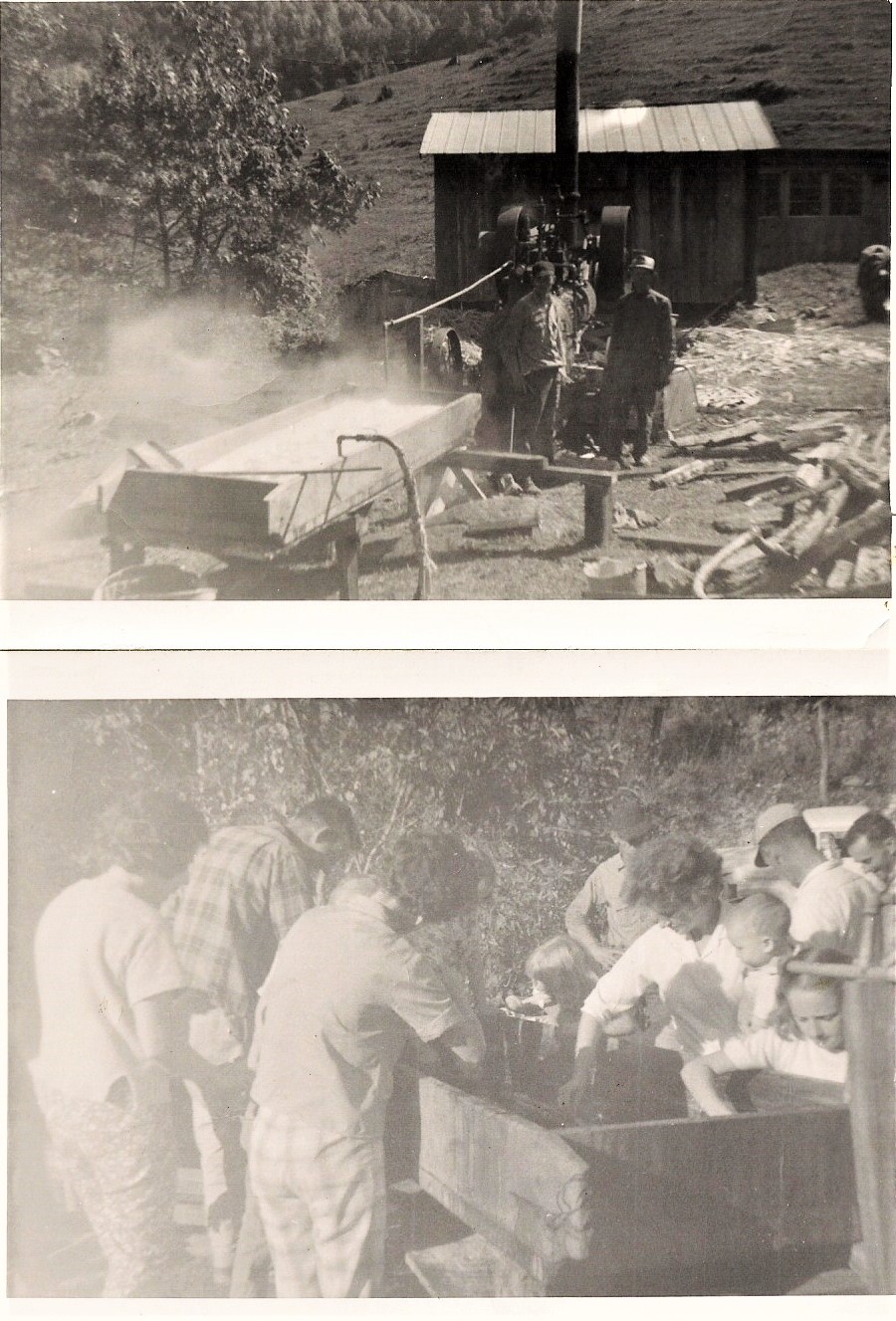

Ask any old-timer and they’ll tell you that a sorghum stir off in the Fall is/was one of the best times of the year. If one of your friends asked if you wanted to go the stir-off, you said, when/where? Besides sharing in the labor they also shared in the fun and dancing as local musicians came to play as did many of the single folk who used this as an opportunity to meet and court.

We’re not certain when, but we believe sorghum cane came over from Africa. And until a couple of generations ago it was a primary sweetener in the South and thus an important part of our Appalachian heritage. When cheap refined sugar became available the hard work and labor made making molasses obsolete.

Technically speaking, sorghum is a grass but looks kind of like bamboo. The first thing you do during harvest is cut the stalk, which grows as high as 10 feet and remove the leaves. Then you take the stalks to the mill where rollers wring them to release the “squeezins” or juice.

Often a horse or mule (see the photo from our friend Jimmie Daniels in Avery County!) was harnessed and walked in a circle to power the rollers.

Unappetizing green foam skimmings are removed during the boiling down process as the liquid gradually turns amber brown. And it’s a bit like cooking alchemy to achieve the perfect sorghum molasses. Remove it from the heat and evaporation pans too soon and it’s not done, remove it too late and it’s thick and bitter.

For those of you keeping nutritional tabs at home, one tablespoon has a third of a gram of protein, a little calcium, magnesium and phosphorus…meaning, sorghum’s good for you!

Most folks I know say the best way to enjoy sorghum in baking is to add a “gullup” or two out of the jug or a spoon full onto hot buttered biscuits. Coming in a close second might be sorghum molasses cookies or Shoo-fly Pie. My personal favorite is a spoonful on vanilla ice cream. Please feel free to share your molasses memories in the comments section below!

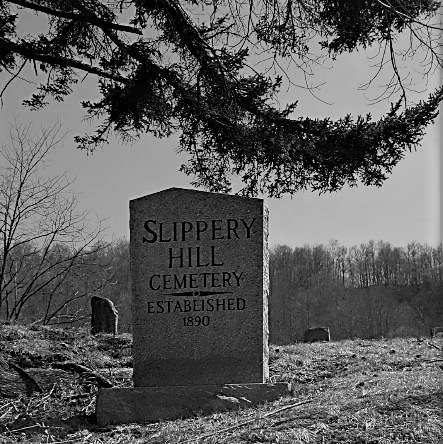

A mysterious graveyard in Slipper Hill

In today’s edition of Appalachian Moments, we travel to a mysterious graveyard in the Slipper Hill area of Avery County, North Carolina.

There have been mysterious lights seen on the Slipper Hill graveyard by different people for many years…a lady known as Aunt Dixie said her mother called them “tokens,” which in Olde English, meant a sign or an omen.

To those who have seen them, the lights appear to be more like a large candle glowing and shining in all directions even more than a bright lantern.

One woman who lived within sight of the tombstones told friends she saw a light, or token at the graveyard…she was in good health at the time, but was it an omen, a beacon, a warning, we don’t know, but she died shortly thereafter. In a fitting coda to her story, she is buried where she reported seeing the light.

In another example, a young woman reported seeing a token above the graveyard a few days before she received word that her boyfriend had died in Italy during World War II. Coincidence?

And while many mountain roads are narrow, several fatal accidents through the years have occurred at that narrow curve beside the graveyard. And more than one vehicle has lost control and/or driven off a 200-foot embankment into the Toe River.

Were those drivers distracted by tokens? Or could there be another reason for the tokens? As we unravel the mystery, consider this: Could it be the curse of Estatoe?

The Toe river doesn’t have anything to do with our feet…it got its name from a young Native American maiden named Estatoe.

The legend, recounted in The Balsam Groves of the Grandfather mountain by the Bard of the Ottaray, Shepherd Dugger, states Estatoe drowned herself in that river because her father, a chief, forbade her to leave with her lover from a different tribe. She rebelled and ran away.

The girl’s tribe chased them until they were surrounded on a high bluff overlooking the river. Escape was impossible.

The young Cherokee warrior tried to push Estatoe back toward her tribe, but she refused to budge.

Placing her hand in his, she stood by his side at the edge of the cliff.

As they stood together, they gave a silent prayer to the Great Spirit, then they jumped, hand in hand, from the precipice, far down into the churning and rocky waters.

From Slipper Hill tokens to the legend of Estatoe… coincidences, who knows? You decide!