I first learned of Horace Kephart when I interned as an undergraduate student at the Western Carolina University Mountain Heritage Center in 1989. Besides being considered one of the most important forces leading to the establishment of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Kephart wrote a fascinating book in 1913 called, “Our Southern Highlanders.” In that book, Kephart had a section that talked about children of the southern Appalachian Mountains and their toys. He wrote that children had few toys other than rag dolls and broken bits of crockery for “play-purties.” I immediately recalled the box of play-purties that my Aunt Donnie kept for us in her hallway closet.

My Aunt Donnie (Donnie Powell Dula) was my Uncle Wayne’s second wife. Aunt Donnie was a true mountain woman and, to hear her tell it, she grew up in a place so far out in the country that the sun set between her house and town. She was elderly, but vibrant. My earliest and most vivid memories of her were the distinctive smell of the Square snuff which she was perpetually dipping; her epic belches that could be heard from 200 yards away; drinking water from her metal dipper, which she kept on a nail above the sink; and seeing how she turned every corner of their rickety, unpretentious house into something thrifty and appealing. Her house was always clean as a hound’s tooth.

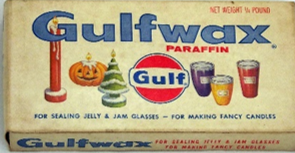

Aunt Donnie loved to cook, and she was an artist when it came to reusing just about any glass container to store canned food. While my mom had always insisted on using regular canning jars and new lids whenever she canned, my Aunt Donnie canned foods in just about any type of container. She used everything from mayonnaise bottles to jars of Sanka. It was a miracle how she could make them seal. Even though she almost always reused the canning lids, and many were rusted or warped, her jars seemed to always stay sealed. And, if the jar wouldn’t seal, she would use it for pickles that didn’t need to be sealed or she used them to can jelly sealed with paraffin wax. She never threw away any sort of metal can either. She would plant flowers in them, and she literally had scores of incongruous cans filling every available space inside and outside of her house. She always had a couple of old containers saved back that I could use for keeping my worms in whenever we wanted to go fishing. However, any plastic containers from margarine to dishwashing soap bottles, she washed out and saved for any children that came to visit since the couple had no children.

Aunt Donnie had a box full of what she called “play-purties” that she kept in the hallway closet. The box was full of all sorts of plastic containers. Maybe it was the effort that she made to save these just for the children in her life, but that box of plastic bottles was magical to me. Whenever we went to visit, we raced to pull out the box of play-purties and we would take them outside to play. We built complex towns and roads, mixing dirt and water, using the plastic vessels as molds. We used sticks and rocks to make the roads and imagined tiny twigs were mighty oaks lining the driveways of our fine mud mansions. At home, the thought of playing with a box of plastic containers was lackluster and boring, but at Aunt Donnie’s, it was fascinating.

My Uncle Wayne died in March of 1981, when I was 11 years old. Mysteriously, it was as if Aunt Donnie had died too, although I later learned that she lived on for several more years. We never once went to visit her after Uncle Wayne died and I never saw her again. In 2013, I went back to the house where she and Uncle Wayne lived. Their house had fallen, but I had a chance to explore a bit. There were scattered rusted rings of abandoned planters and overgrown flowerbeds, lost to neglect. I found one of Aunt Donnie’s old snuff cans and I have it saved among my precious memories. The box of play-purties was gone. I guess somebody probably thought it was trash, but they couldn’t have been more wrong.