WALT’S CAMPFIRE 6-19 #1

copyright Walt Hampton 6-1-19

RATTLER!

Over the course of the next thirteen weeks I have been given the opportunity to share with you some more time around the campfire, while I take a deeper look at our Appalachian mountains. My intention is to stimulate some thought and conversation on our home, and its history, natural and cultural, and the resultant impact on our lives. I have to preface this with my bias: I love Appalachia and having lived in several other areas of the country, I cannot imagine living anywhere else now. I will do my best to be objective but you should know ‘up-front’ you are dealing with a mountain boy with the New River in his veins. There will be no apologies for that.

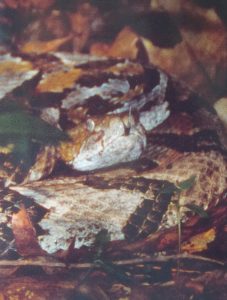

When you consider a landform that has been with us over millions of years, you can expect a diversity of living things to be found there, as those living things evolve to better utilize the resources at hand, and to fit into the inevitable opportunities that changing climate and vegetation over time may bring. Certainly the Appalachian chain is well-known for its natural diversity and the presence, abundance or absence of species over time can be a strong indicator of the health of the ecosystem as a whole. Even the most noxious or repugnant of species can tell us a great deal about the stability of an ecological system and perception is the key here: what one person may view as a noxious critter may in point of fact be a critical factor in the health of that ecological system in question. If you are looking for a critter that evokes a visceral reaction from the most people concerning living things, I do not think you can do better than snakes generally speaking, and rattlesnakes specifically. While they can be understood and even admired, the rattlesnake does not generally evoke much love.

As an elective for my wildlife management degree I studied herpetology under Dr. Sandy Echternacht and Dr. Joe Mitchell at the University of Tennessee. In our study of reptiles and amphibians we concentrated our focus on those species found in the Appalachian chain, for their great diversity and rarity. Of those many species the timber rattlesnake, Crotalus horridus, held a special fascination for me. Our Appalachian folklore is full of tales of this predator, from the tantalizing to the ridiculous. One thing is for sure; if you ever encounter one under surprise circumstances (and most rattlesnake encounters are one hell of a surprise, believe me), you will never forget it.

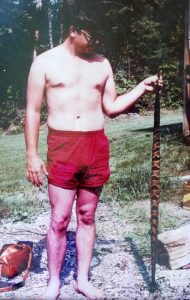

From 1978 to about 1988 I lived on the north face of the Iron Mountains near the tiny community of Camp, Virginia. During the summer of 1983, in the course of my work for the Virginia Game Department on National Forest land, I kept a careful record of my daily activities and from May until August I met up with 26 timber rattlesnakes within 5 miles of my home, including one that took up residence in my woodpile beside my house. That snake would warn me every morning with his rattle when I went to start my truck, and finally while mowing the lawn one day I caught up with him as he crawled from the woodpile to my porch. While I usually did not kill the rattlers I encountered far from the places people would frequent, in this case with pets and children on the way, I felt it necessary to initiate hostilities. There wasn’t anything evil or nasty about the snake, he was just being a snake, but unfortunately for him, in the wrong place at the wrong time. Later in my career I would be involved with radio tracking tagged canebrake rattlers (a subspecies of the timber rattler) in eastern Virginia, that seemed to be disappearing. The ecological web that study indicated was profound, and in a nutshell, here are the results: Canebrake rattlers are specific predators of gray squirrels; gray squirrels in that region depended on white oak; white oak reproduction was being eliminated from forest stands by the browsing of overpopulated deer; if the forest was cut or lost to hurricane or some other natural disaster, the oak component would be eliminated, the squirrel population would crash, and presto, no more canebrake rattlesnakes. Isn’t it funny how seemingly unrelated things fit together…

In our area of the central Appalachians the population of timber rattlesnakes seems to be stable and not requiring special protection. Not so in some northern states, where development and encroachment have destroyed habitat, and the rattler has disappeared or is in danger of extinction. Let me make it clear; I do not love rattlesnakes, but I don’t want them gone. They have a place in Appalachia and with proper management, we can be neighbors far into the future.

For more information on the timber rattlesnake, contact the Virginia Herpetological Society at their website.