[Author’s Note: This story is true but is what I call “faction,” in that every branch of our family has been told of it so we know it to be true. The details vary, however, depending on whether the story teller is an older family member & closer to the generation in which the accident occurred. I’ve taken very little creative licensing with its telling but have combined the details told by my aunts & uncles.]

I stood in the midst of the tiny Appalachian family cemetery devoid of an arch with an identifying family name, and saw that the sum of the beautiful but ancient headstones numbered fewer than thirty. The small plot was wrapped in rusty barbed-wire fencing strung between rough-hewed branches and was barely strong enough to discourage the nearby grazing cattle. No additional soul had joined the other family members buried at the top of this hill since 1940 with most buried in the early 1900s. Leander, a man born of Irish descent, is buried here. His twenty-year-old son and wife, who died in 1898 and 1940 respectively, rest beside him.

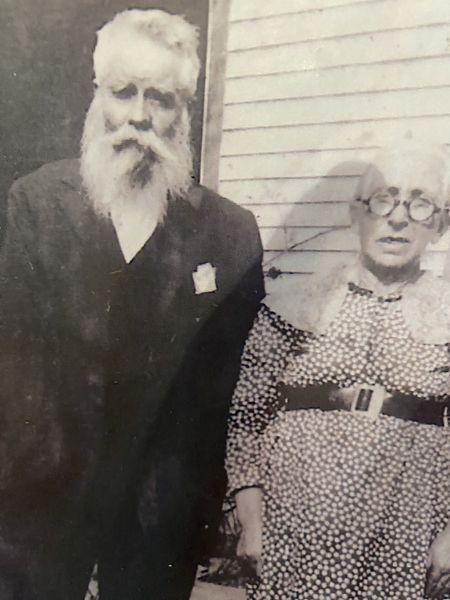

Leander raised sheep, tended his apple orchard, briefly served as a sheriff and was a timber man. His great joy, however, was to play his fiddle. And, as was the case for many old-time players at the turn of the century, his fiddle rested low on his chest rather than against his chin, and he’d play with big sweeping movements. He was well known for his music which was often heard throughout the narrow valley where he lived, and he particularly enjoyed playing on his porch at evening time. He knew & loved the old ballads and played them with the touch & soul of a master. But, on many occasions, he’d also play tunes that had those on the porch jumping up and flat-footing along its narrow width raising dust motes and laughing from the fun of it.

No one today remembers exactly when the long ago tragedy occurred, but it must have been before the youngers were old enough to remember the trauma. They never heard their elders talk of the occasion except that it happened after the laurel and blackberries were in bloom. Leander and a crew of men had taken the portable sawmill up to a stand of thick chestnuts to work its timber. It was a comfortable day of mild temperature & hours long enough to get plenty done. As the foreman, Leander was standing close by to watch for any irregularities but, by the time that he became aware of the impending danger, the accident happened. The saw blade hit a hidden knot on the trunk causing it to jump and twist towards him causing a great injury. The flurry of activity following that emergency moment was told often into the winter months as the men stood together at church or around the store’s pot-bellied stove.

Leander’s right arm was almost severed and the urgency of getting him off of the mountain & down to the doctor was obvious but was only accomplish by the use of one of the mules which had pulled the sawmill to its current site. To make matters worse was that Its owner was not at all agreeable for his mule to be whipped into a frenzied journey so quickly after hauling up the mill. He finally relented under duress and the others did their best to bind up the wound for the journey. He survived but, unfortunately, Leander did lose his arm. He was courageous in the recovery and never uttered a complaint but, instead, spent his words on generous praise and thanks for those who aided him & his family.

It was determined that the arm which once offered songs such as the mournful “Barbry Ellen” and the quick “Old Joe Clark” should be properly laid to rest. So, it was buried in his fiddle case with solemn respect and under the lone shade tree not far from where he rests today. And, though, he was often heard to hum the old tunes while keeping time with his toe, the spirit of his music was lost along with the history of other fiddlers such as himself.