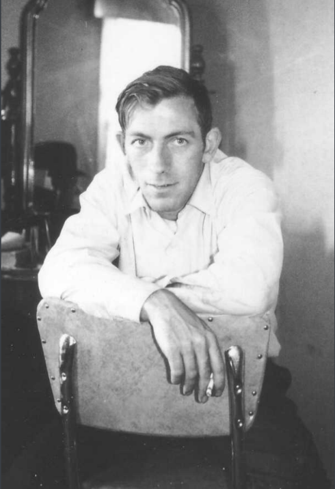

Not every family has an Uncle Edsel and that’s probably a good thing. My great-uncle Edsel Church was my Grandpa Bynum’s brother. They were eerily similar in their good looks and in the way they talked. Although they grew up in Boone, Uncle Edsel lived in Caldwell County for as long as I can recall. I don’t ever remember visiting him, or meeting his wife or children, or even seeing him anywhere other than at our house. Every so often, Uncle Edsel would show up at our house, and though he would try to act sober as a judge, he was always about half-lit when he did. Yes, he loved to drink, and he was good at it. Uncle Edsel was a real character and we all loved him so!

Uncle Edsel would roll up about once a year, always in a car as flashy as a rat with a gold tooth, certainly more stylish than anything we had. Each time, it seemed like his primary motive was to borrow the phone to call somebody long distance and he would somehow reverse the charges. I’m not sure how he did it, but the phone company doesn’t seem to offer that service anymore. He would call the operator who would connect his call. At the end of the call, the operator would come back on the line and tell the caller how much the call cost. Uncle Edsel would then pay my parents for whatever expenses he had incurred. Whenever Uncle Edsel came to visit, he always carried cash, brought plenty of liquor, and his sideburns were neatly trimmed and recently doused in too much Old Spice. His cologne bath didn’t cover the distinctive smell of cigarette smoke that permeated every stitch of his clothing, but it was strangely pleasant all the same.

On one visit, my little brother Glenn and I happened to be outside when he drove up in his long, turquoise LTD Ford. “Hey boys, you are just who I was looking for,” he said. “We’re going to make some money!” That was all he had to say, and we both smiling like goats in a briar patch. He got out of the car and opened the trunk. Inside, there was a box with a dead red fox that had been run over by a car. It wasn’t a recently dead fox either; it had to have been a couple of days old. Uncle Edsel insisted that this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get rich! “Do you know how much a red fox hide is worth,” he exclaimed with slightly slurred speech, “Why, at least seventy-five dollars!” We grabbed the leaking box and headed towards the porch yelling ahead to let everyone know that Uncle Edsel had cut us in on a fortune. All we had to do now was skin the fox and figure out where to cash in our pelt.

Supper was already on the table and Uncle Edsel said it was a bad idea to engage in fox skinning on an empty stomach and besides, he was mighty thirsty after that long drive. Over dinner, we discussed the ins and outs of the exceptionally lucrative fox hide trade. My mom mentioned that perhaps the fox had been dead too long and that maybe the hide wouldn’t sell. It was hard to fathom how she could be so naive! We had a fox skinning expert in our presence and my seven-year-old little brother had already figured out what we were going to buy from our first five hundred skins. We still hadn’t nailed down exactly where the fox hide market was, but there had to be one. How else did those women from town, who had more than they could say grace over, get exquisite fur coats made from rare red foxes?

By the time supper was over, Uncle Edsel was full as a tick. My brother and I could hardly contain ourselves, but Uncle Edsel was three sheets to the wind and had to hold onto the furniture as we headed outside. Even so, his thirst had not been quenched and he kept on drinking. We started sorting out how to separate the fox from his skin on the front porch. Mom didn’t approve, so we moved around back. It did indeed smell bad and we didn’t even have our skinning knives out yet. Uncle Edsel explained that skinning fox hides for resale required special care. You couldn’t tear or cut the hide and you had to scrape the inside to make sure that it would dry properly. He told us exactly how to proceed. Soon, the gases inside the dead fox began to escape and the stench intensified. Did I mention it was summertime? The mind is strong, but the body is sometimes weak, and I’ll admit, I didn’t last long. Glenn, however, was determined, and he whittled away with his dull knife with sagely encouragement from Uncle Edsel. In about an hour, the now tiny fox, was freed from his hide and Glenn was grinning like a possum eating persimmons. Uncle Edsel’s enthusiasm had diminished noticeably, but he continued to insist that the extensive damage suffered during the unfortunate car accident probably wouldn’t matter. Glenn was triumphantly covered in unknown pathogens and we both smelled worse than the fox, if that was possible.

Having strategically avoided actually touching anything fox-related, Uncle Edsel went to sleep on the couch. Mom treated us like polecats at a camp meeting, so me and Glenn got hosed off outside. We had already agreed that Glenn would be in the rewarding skinning business by himself and that I would seek another path to fortune. When Uncle Edsel woke up the next day, he agreed to carry the hide to market and slipped me and Glenn a couple of dollars each. We never heard whether or not the fox hide sold, but we were careful to be on the lookout for any other roadkill treasures. Uncle Edsel has been dead and gone for almost two decades, but not his precious memory. When I close my eyes and concentrate, I can still smell the day Glenn and I were in the fox hide business.