Over a long career as a wildlife biologist for state, federal and private interests I have had the wonderful opportunity to work in some starkly different habitat types. From our beautiful Appalachians to the low-country coastal swamps, it has been an education every day. But it was not until I worked in Texas that I fully realized that it is water that means life. Water, my friends, is everything.

When the first humans arrived in North America they followed the watercourses and game trails to explore the new ground. Just as they located their habitations along these watercourses so did the later Appalachian pioneers. The rivers were highways and on their shores we built the cities, and along the creeks and springs were the towns and communities. Water provided transportation for goods and the energy needed for processing those goods. All along the creeks and rivers sprang up the tanneries, grist mills and eventually the manufacturing factories. Water made it all happen.

When the first humans arrived in North America they followed the watercourses and game trails to explore the new ground. Just as they located their habitations along these watercourses so did the later Appalachian pioneers. The rivers were highways and on their shores we built the cities, and along the creeks and springs were the towns and communities. Water provided transportation for goods and the energy needed for processing those goods. All along the creeks and rivers sprang up the tanneries, grist mills and eventually the manufacturing factories. Water made it all happen.

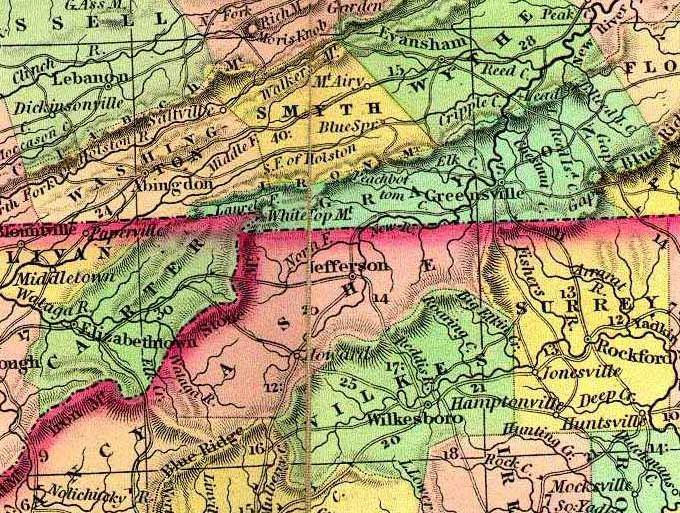

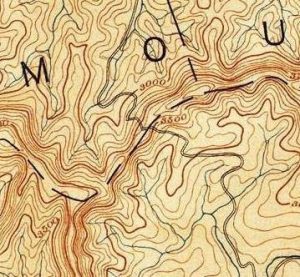

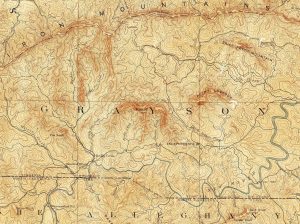

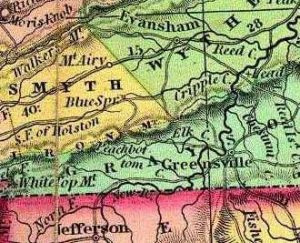

Where I live we have two major river system drainages, that of the New River (which arises in North Carolina, in two branches) and that of the Holston River (which has three branches, ours being the South Fork). These are separated by a divide, that roughly runs east/west along the Iron Mountain range and then north through Glade Mountain into Big Walker Mountain. Both of these systems drain eventually into the Mississippi River. An area of highlands on the north face of the Iron Mountains provides a system of springs that create the South Holston branch, and you can probably be safe in saying that Blue Springs in Smyth County is the headwaters of this branch. Just a short distance east and across this divide from the Blue Springs, you find Cedar Springs, which is the headwaters of Cripple Creek, and it feeds into the New River.

The first explorers to the Appalachian region used the watercourses to penetrate the wilderness, following upstream to the headwaters of the rivers and creeks, then crossing the divides and ‘gaps’ in the mountain ranges to enter the next drainage. These paths across the mountains became roads and we can see today where these first explorations took place; as time progressed we improved these roads and they became the highways of today. In colonial times in Virginia it was a requirement of the county courts for residents to build and maintain the roads as delineated by the court. One of these roads, that connected Blue Springs on the north side of the Iron Mountains with the Elk Creek drainage on the south side, was one of the first mentioned in Grayson County records.

In those days it must have seemed a monumental task to view the impenetrable range of mountains and seek a place to cross; in this regard the settlers used the trails established by the Indians and big game, notably the eastern race of American Bison, through the low points in the ranges, once again following the creeks upstream into the mountains to get to these low points. These low points are called ‘gaps’ and even today that word is common in our reference to place names, such as Low Gap, Roaring Gap, Deep Gap, Ward’s Gap and Blue Springs Gap to name a few. It is this Blue Springs Gap that although is still being used today, most nearly remains in an undeveloped status.

In the second road order issued by the Grayson County court, that order reads in part

“…Ordered that Dennis Fielder, Lewis Hale, Rebin Cornett, and William Long be appointed to view the grounds, and after being sworn to view the grounds proposed from the Blue Springs Gap to Richard Wright, Jr.’s and make report to the next court whether the same can be made a wagon road.”

This order was made in 1793. In the accompanying maps one can find this road trace where it crosses from Smyth County on the north (look for the tiny community of “Camp” near the Grayson/Smyth/Wythe county line) to Grayson County to the south, and as can be seen in the order, was the consideration whether improvement of an existing ‘bridle path’ or trail from the gap into Grayson County to a point near the headwaters of Elk Creek was possible. In our discussion of ‘water’ for this column, it is important to note that this road construction was to connect two water sources (Blue Springs on the North side of Iron Mountain to Elk Creek on the south side) because that is where the settlements were at that time. Since the Holston drainage runs east to west into Tennessee, this connection would give early Grayson County residents access to this western migration and trade route that was otherwise blocked by the formidable Iron Mountain range.

This order was made in 1793. In the accompanying maps one can find this road trace where it crosses from Smyth County on the north (look for the tiny community of “Camp” near the Grayson/Smyth/Wythe county line) to Grayson County to the south, and as can be seen in the order, was the consideration whether improvement of an existing ‘bridle path’ or trail from the gap into Grayson County to a point near the headwaters of Elk Creek was possible. In our discussion of ‘water’ for this column, it is important to note that this road construction was to connect two water sources (Blue Springs on the North side of Iron Mountain to Elk Creek on the south side) because that is where the settlements were at that time. Since the Holston drainage runs east to west into Tennessee, this connection would give early Grayson County residents access to this western migration and trade route that was otherwise blocked by the formidable Iron Mountain range.

When Cecelia and I were married we built our first home on this Blue Springs Gap Road (State Route 798) in the community of Camp in Smyth County, and in fact ours was the last house on the road before it crossed into National Forest for its climb to the gap. If I wanted to travel from home to Comers Rock, the tiny community on the south side of the mountain in Grayson County where the road ended, I could either drive the long way around east to Speedwell, cross the mountain in the Route 21 gap, and then west up Elk Creek, a distance of over 35 miles, or just take the old trail over the mountain, which was a distance of about 10 miles. If you were on foot or on horseback, which would you take? The original road in a very undeveloped state is still there and a drive up and over the gap is a real eye-opener, in terms of what early travel in the mountains must have been like, and the obstacles faced by our pioneers. Once the gap is crested a new world opens up.

Probably our greatest natural resource in the central Appalachian region is the water supply, both surface water in the form of our rivers and creeks, and our abundant supply of pure underground water from the mountain aquifer. In a land of thin mountain soil and short growing seasons this availability of water made subsistence agriculture possible, giving our pioneer ancestors a toe-hold in the region, and made possible trade and migration routes by following the branches of the surface water. If not for the water, what would the Appalachians be? In a later column we will look closely at our water resource and what we are doing, good and bad, with it.

The next time you are speeding down some road, headed to that important appointment, glance out the window and look for the water; I would wager you see it differently now than you did before.