The Appalachian region of our country has a unique and storied past. This is an area of exploration, settlement, abandonment and re-settlement that today is becoming popular with the folks wanting to ‘get back to the land’, either by retiring here or visiting in a semi-permanent fashion, with summer homes or camping lots. There has always been something about the Appalachian Mountains that has drawn people here; in the beginning it was simply land that poor folks could afford, a place to live that the rest of the world seemed to ignore and pass by, land too poor for any serious interest. Coal and timber changed that, at a time when the growing nation needed those resources. Now we are sought out by people looking for something missing in their lives, something most cannot articulate or understand; I believe it is a desire for a simple connection with the land.

An old friend and I were working on my ancient hunting car and had to travel to town for a few parts. It was a late-August morning and the mist along Crooked Creek had about dissipated with the warming of the sun. As we cut through the Carroll County back roads between his farm and town we came over a hill and there to the right, some distance down in the field away from the road, I saw a dozen doves sitting on a power line. Without me saying anything, my partner, who was driving, said “I wonder if anyone has cut any corn yet.” Without exchanging any words we both had seen the doves; because both of us are Appalachian born and raised, in families that hunt, and because we both knew that the dove season opener was only a week away, we had been watching for such things. That we were watching is the point.

An old friend and I were working on my ancient hunting car and had to travel to town for a few parts. It was a late-August morning and the mist along Crooked Creek had about dissipated with the warming of the sun. As we cut through the Carroll County back roads between his farm and town we came over a hill and there to the right, some distance down in the field away from the road, I saw a dozen doves sitting on a power line. Without me saying anything, my partner, who was driving, said “I wonder if anyone has cut any corn yet.” Without exchanging any words we both had seen the doves; because both of us are Appalachian born and raised, in families that hunt, and because we both knew that the dove season opener was only a week away, we had been watching for such things. That we were watching is the point.

In his landmark work A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold, the father of modern wildlife management philosophy, wrote a short essay on a casual social experiment he conducted at his hunting cabin. Dr. Leopold cut a swath through the dense brush from his front yard down the hill to the creek. He found that on frequent occasions the deer that called his farm home would appear in the cleared swath, deer that he otherwise would not have seen without the linear opening. He placed some chairs in that front yard and carefully observed his visitors when he and his dog had company, when he casually suggested they sit outside and enjoy the Wisconsin summer weather, and how those visitors would orient themselves relative to the deer swath. To paraphrase his observations, he said his visitors, as an unconscious act based on their individual experiences, each placed their chair in a different aspect: the deer hunter sat so he could watch the swath; the duck hunter sat so he could watch the horizon; the bird hunter watched the dog; and the non-hunter did not watch.

I wonder how many people driving down Carroll County’s roads today would have noticed those doves…

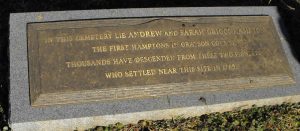

What Dr. Leopold was trying to articulate is that as we progress into ‘civilization’, we grow further away from the land, and the loss of this land ethic, as he called it, was the sure destruction of true conservation. What we are losing in the Appalachian region today is more than small farms, old cabins and neglected cemeteries. We are losing an ethic and outlook on life that was imprinted on our people by necessity: in the old days if you wanted to survive life in the mountains you had better pay attention to the world around you, and this attention was based on the reality of life and the need for planning and preparation; an individual responsibility that we seem to want to relinquish today. So many people coming to our region today harken to the “good old days” and speak of those days in wistful tones; I wonder how they would feel, sitting in the light of a coal-oil lamp by a woodstove on a snowy mountain night, holding a child whose cough was worsening or whose fever would not break. If one is going to fall in love with Appalachia, and truly appreciate the region, we must be honest in our assessment of mountain history and the connection of mountain people to the land.

What Dr. Leopold was trying to articulate is that as we progress into ‘civilization’, we grow further away from the land, and the loss of this land ethic, as he called it, was the sure destruction of true conservation. What we are losing in the Appalachian region today is more than small farms, old cabins and neglected cemeteries. We are losing an ethic and outlook on life that was imprinted on our people by necessity: in the old days if you wanted to survive life in the mountains you had better pay attention to the world around you, and this attention was based on the reality of life and the need for planning and preparation; an individual responsibility that we seem to want to relinquish today. So many people coming to our region today harken to the “good old days” and speak of those days in wistful tones; I wonder how they would feel, sitting in the light of a coal-oil lamp by a woodstove on a snowy mountain night, holding a child whose cough was worsening or whose fever would not break. If one is going to fall in love with Appalachia, and truly appreciate the region, we must be honest in our assessment of mountain history and the connection of mountain people to the land.

Over the course of the next few weeks we will in this column explore the Appalachian ethic and mindset, and see what we can learn from the people that forged their lives from the varied elements of these mountains. We will attempt to visit those folks up the holler, to sit on their porches or help them with their chores, or join them fishing and hunting, and I will jot down just a few observations, perhaps a perspective from an Appalachian writer you may not have considered. We will climb the mountain and float the river and I invite you to sit in my chair, and to see what I see-and just maybe you will catch a glimpse of the Appalachia I hold so dear, and why I know that its preservation must be pursued.

© 2018 Walt Hampton